Photos of Pre-Revolution Russia In Stunning Color

Long before color film, these images captured the beauty of the Russian Empire with vivid hues.

Even in the 1940s and 1950s color photography wasn’t common. Color film was expensive and rare and many publications only printed in black and white anyways. Even the first years of television were only broadcast in black and white. So it’s normal for us to think about the early 20th century as a period when color photos simply weren’t available. But, that isn’t exactly true. Various methods for creating color photographs were in existence before World War I, as these color photos of pre-Revolution Russia show.

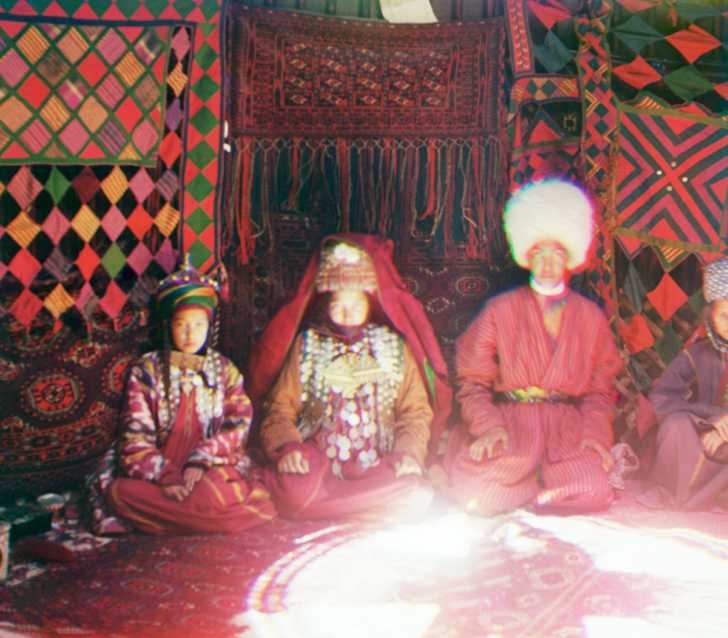

One method for achieving color photos at the time was based on the 3-color principle. A single subject would be photographed using 3 different filters: a red one, a blue one, and a green one. When displayed together the colors overlapped to create a multi-hued image that recreates most of the colors of the scene as perceived in real life by the human eye.

This method is laborious as each photo must be taken 3 times to complete the process. Some cameras had mechanisms that made it easier, but were prone to unique problems of their own. Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky, a man of Noble birth in pre-Revolution Russia, was a member of the oldest photography association in the empire. He favored the 3-image method for creating his color photographs and was commissioned to take thousands of these early color photos for Czar Nicholas II after a screening of his color photos greatly interested the czar, who wanted to see the Russian “motherland” represented through color photography.

The czar wanted the beauty of rural Russia and her colonial outposts to be documented for posterity, but for Produkin-Gorsky the aim was far broader. He wanted his images to be made into “optical color projections” that could be used to educate school children. He developed the images in a mobile darkroom located in a railcar that was supplied to him by the czar.

He was also issued serval permits that allowed him access to restricted areas for the purpose of documenting the empire. Between 1905 and 1915 Produkin-Gorsky took thousands of these color photos, capturing a world soon to be lost to revolution and war.

The idealized life of Russian peasants in the countryside was one subject repeatedly revisited by Produkin-Gorsky. While the photos do indeed show some breathtaking scenes, the farmers and working classes of the Russian Empire were not living carefree lives, instead toiling for meager meals and often suffering winters in subpar homes. Had the commoners been pleased it is doubtful that the Revolution could have even gotten started.

By 1918 most of the Russian royal family had been murdered and the Bolshevik Revolution was well underway. In the early 1920s Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky relocated to Paris, and the thousands of photos he took in Russia, Georgia, Uzbekistan, and other locations went with him.

In 1948 (4 years after his death) the collection of Prokudin-Gorsky’s photos were purchased from his heirs by the Library of Congress. Using specialized digitizing software in the early 2000s, many of the imperfections that arise from the 3-filter color process have been removed. But, you can still see artifacts of this method in some of the photos.

When you look at certain of his images you can see a slight fuzziness to the colors, almost like looking at a 3D image without the special glasses to correct the scenes. This is because some aspect of the subject changed between when the 3 different images were taken. The blue area might outline a slightly different area than the red in an instance like this, creating less-defined colors and shapes or even double images.

Today these stunning photos capture a time long lost to history. Thatched roofs top the cottages that sit on the edge of a field of Russian poppy flowers. The emir of Bukhara sits robed in silk jacquard and holding a sword. 3 young women in traditional garb seem to solemnly present plates of food to the viewer. These are images that are not reproducible as many of the customs and much of the architecture seen in the photos no longer exists today.

Not only do these photos record a world long gone to time, but they also show just what is possible when ingenuity and industry are employed by someone with a true passion for their work. Produkin-Gorsky was trained as a chemist and dedicated the majority of his working years to photography. This archive of early color photos is a testament to his vision and to his hard work.

SKM: below-content placeholderWhizzco for DOT