Book Found in Closet Turns Out to Be Valuable Logbook of a 1700s Slave Ship

Records like these are extremely rare.

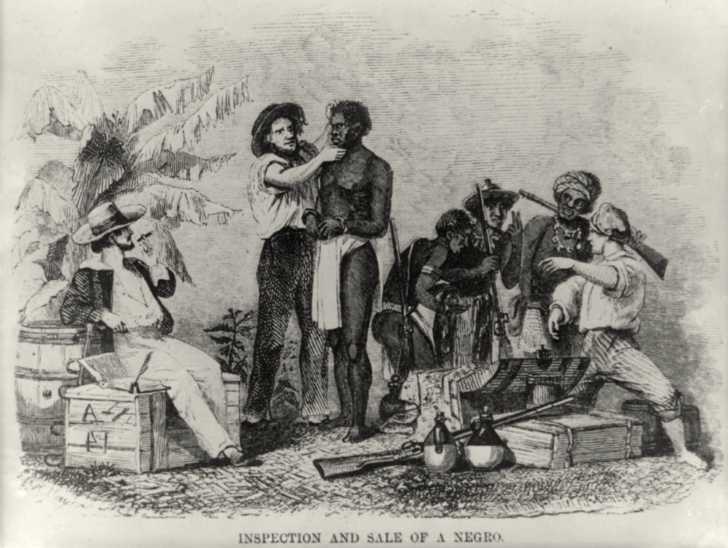

The effects of the Trans-Atlantic slave trade are evident the histories of many countries in the world. The enduring infamy of hundreds of years of trading in enslaved peoples is a legacy of cruelty, but one that is often unknown.Recently various collections of slave trading records have recently been digitized, giving new insights into how the captured were treated and where they came from.

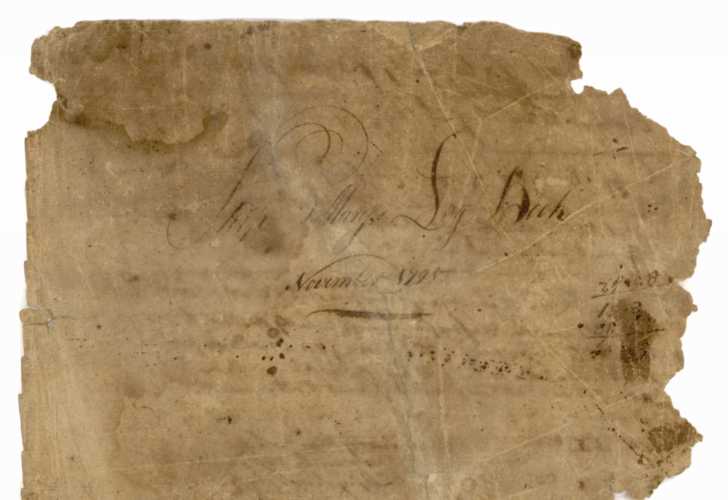

The ship record of the slave ship, Mary, was recently digitized by Georgetown University. The record dates from 1795 and the ship’s captain at the time was John Sterry. The ship’s owner (the financier of the trip) was Cyprian Sterry. The vessel departed from Providence, Rhode Island, on November 22, 1795. Despite the Trans-Atlantic slave trade having been restricted in Rhode Island in 1652 and again in 1774, slavers from the area controlled between 60 and 90 percent of all incoming slaves in the U.S. during the period.

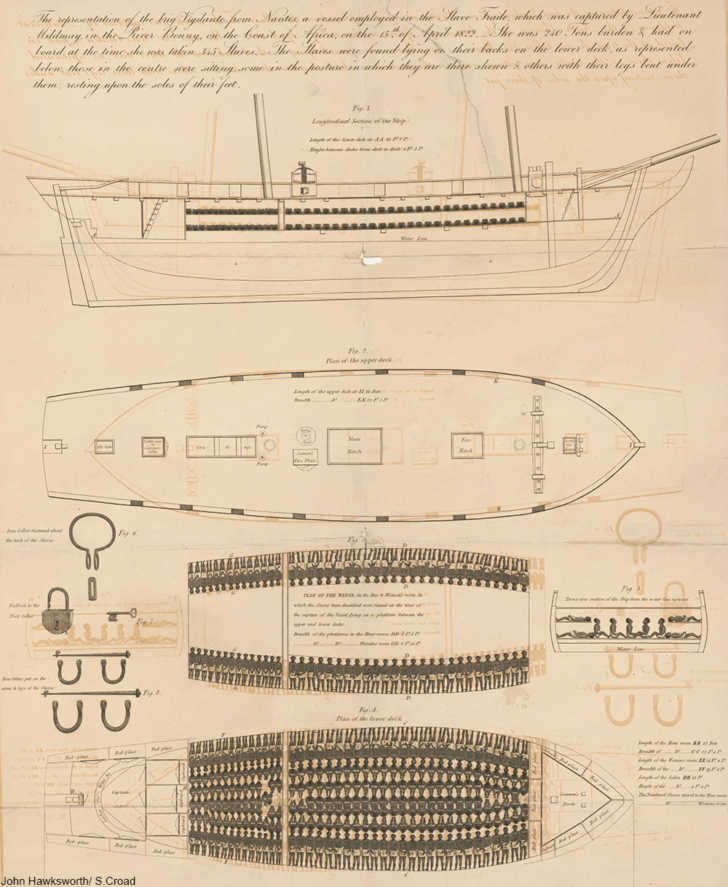

Simply put, the laws on the slave trade were not enforced in Rhode Island at the time, allowing for large ships like the Mary to continue importing slaves from West Africa, the Ivory Coast, and the Gold Coast. But, the Mary did not deliver enslaved people back to Rhode Island, instead bringing them straight to the plantation-heavy state of Georgia to be sold.

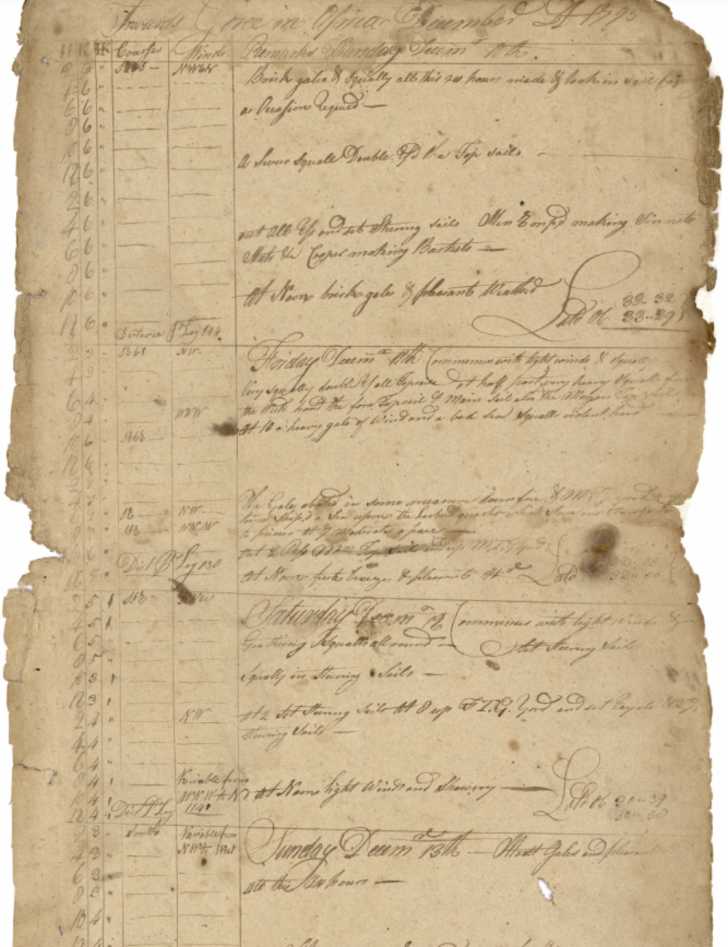

We will never know the names, ages, tribes, and subsequent histories of the kidnapped people aboard the Mary. But, we do know from the logbook that 38 of them never made it to Georgia. The causes of death for the unnamed enslaved aboard the Mary included suicide, infectious diseases, and severe discipline and execution by the ship’s crew for misbehavior.

Only a week after leaving the western coast of Africa for the final time, 4 enslaved men were killed after they had escaped their shackles and attempted to take control of the ship. Months later 3 members of Captain Sterry’s own crew attempted the same, adding the murder of the captain to their agenda.

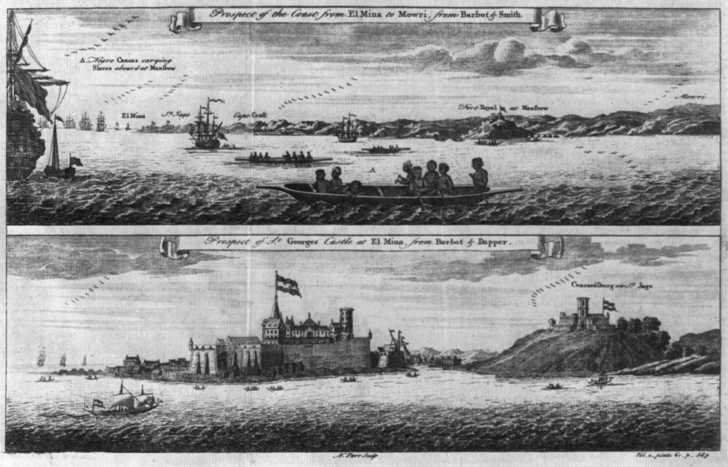

At each stop along the slave route, the Marywould stop at so-called slave castles. These forts were built for the explicit incarceration and trading of kidnapped Africans, streamlining the lucrative business of international slave trading.

Slavery in the U.S. was legal until the Civil War, but from 1808 onwards bringing new slaves imported from outside the U.S. was illegal. So, what became of Sterry’s business? Only 2 years after this logbook was created, the Providence Abolition Society sued Sterry for violating the law and won. His last slave ship voyage was completed in 1797.

The Mary logbook is one of an emerging series of records about the Trans-Atlantic slave trade. This book was found in a closet in the California home of Robert S. Askew, who reached out to a friend and alumnus of Georgetown University, where the book was later donated.

Since the donation the book, which was in bad condition, has been restored. A text version may soon be available, but for now you can study each page in the elaborate 18th century script of the captain’s assistant.

For more information on the slave trade, you can visit the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, one part of a growing body of work attempting to shed light on the details of this gruesome period in world history that erased the names and pasts of an estimated 12.5 million Africans.

SKM: below-content placeholderWhizzco for DOT