It Took Crowdsourcing to Crack Code Charles Dickens Created in the 1830s

His squiggles are still being unraveled today.

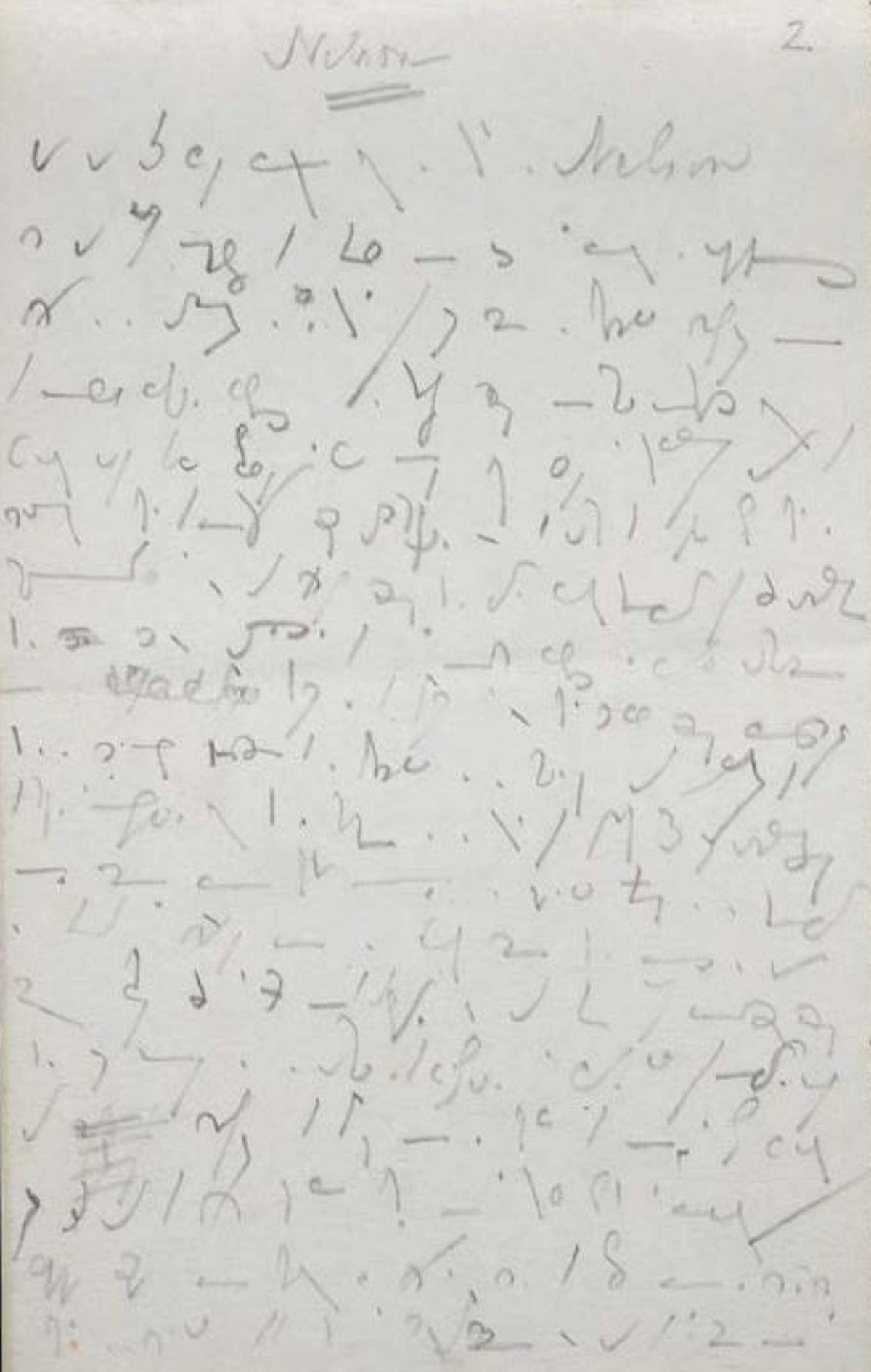

Charles Dickens is most famous for writing stories such as A Christmas Carol, Oliver Twist, Great Expectations, and A Tale of Two Cities. But, in his lifetime he finished 15 novels, finished many serial stories, and was an unstoppable letter-writer. He was also an editor as well, and his literary production didn’t end there. He also invented his own stenography-type shorthand. It was such a good code that people are only just now deciphering it- 150 years after Dickens’ death.

Dickens created his code between the 1830s and 1860s, having learned Gurney’s system of shorthand around 1830. He used his own shorthand for stories and documents that he never intended others to be able to read. In this way he maintained some of his privacy. He called the code his “devil’s handwriting” and it consisted of various symbols- not unlike traditional stenography. While his method was unique to him, he did borrow some symbols from the Gurney system, such as the round shape that means “the world”.

This meant that sensitive documents, new stories he wasn’t ready to publish yet, and personal letters could all be encrypted in writing that only he could understand the meaning of. In the 1850s he met a young actress named Ellen Ternan and their extra-martial relationship was kept secret for many years until after the death of his last children. Ternan was one of the first beneficiaries listed in Dickens’ will. In this light it makes sense that the ever-thinking and ever-writing Dickens might have relished using a shorthand that no one else could translate.

For years many different people have been trying to figure out this seemingly-unbreakable code. The Dickens Code project has sought to bring these symbols into the light and has made many public calls for members of the public to try their hand at deciphering the code.

In December of 2021 they even offered a small reward of £300 to the person who could crack the remaining symbols written in the “Tavistock Letter”. To date the letter is around 70% completed thanks to crowdsourcing.

This looks fun. Researchers have set a deadline of New Year’s Eve to crack the code of Charles Dickens’ Tavistock Letter, with a £300 prize to anyone who can fully or partially decipher it. pic.twitter.com/xlTJ59Ho4X

— ABDecker (@decker_ab) November 20, 2021

The prize money went to IT worker, Shane Baggs of San Jose, CA, as he contributed the most characters to the work. The runner up was Ken Cox. There was also an effort in 2011 to crowdsource the deciphering work, publicized by the Morgan Library & Museum in New York.

Philip Palmer, Curator, and Head of Literary and Historical Manuscripts at Morgan Library & Museum, said that, “Having the text of this letter at long last will allow scholars to learn more about Dickens’s shorthand method while gaining further insight into his life and work. We are thrilled that colleagues at The Dickens Code project have helped make this letter accessible in new ways to researchers.”

Other Dickens works that have been partially deciphered included the short story, “The Two Brothers”, and an essay on morality by Sydney Smith.

Now, The Dickens Code project has announced another call to action for help deciphering a work written by Dickens’ shorthand student, Arthur Stone, simply titled, “Nelson”. You can find out the details of this most recent challenge here.

SKM: below-content placeholderWhizzco for DOT