Some Enslaved People Earned Money- And the Reason Might Shock You

This dark chapter of American history still has much to teach us.

In the chattel slavery system of the American South, slavery was maintained through the high birthrates of enslaved persons since the actual importation of enslaved people was outlawed in 1807. Those born into slavery had no experience with other ways of other life and the whims of the masters were imposed on them at every turn. Slave holders in the U.S. were maximizing their profits any way they could and their penny pinching led to a surprising turn of events: enslaved people earning money.

The Clothes Make the Man

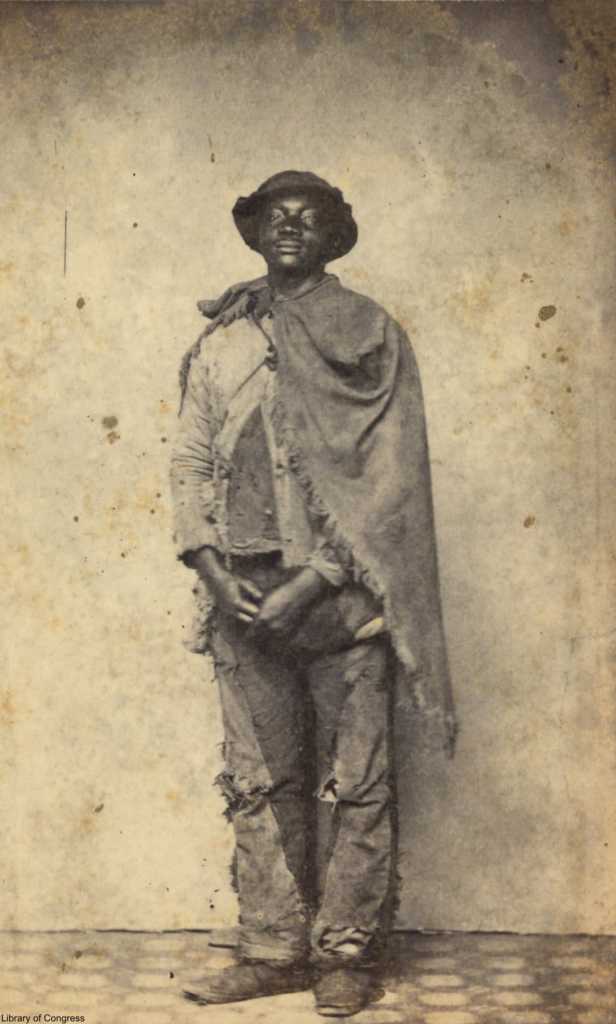

On the plantation enslaved people were given 2 allotments for clothing per year. The exact dole varied by region, wealth of the plantation, and by job duties and status. Field hands were often given only osnaburg fabric, a coarse unbleached linen. Sometimes they were outfitted in linsey woolsey (wool and linen coarse weave), denim, or homespun fabric which could be of varying quality. Coarse flax fabric was particularly painful to wear before it had been broken in, yet this was a common material for enslaved people.

Indoor ladies maids often were given better allotments which consisted of finer fabrics, some decoration, and higher quantities of supplies. Sometimes they were given shoes or shawls or blankets, but this was not always the case. Hand-me-downs were sometimes given or willed by the master upon his death to favored servants.

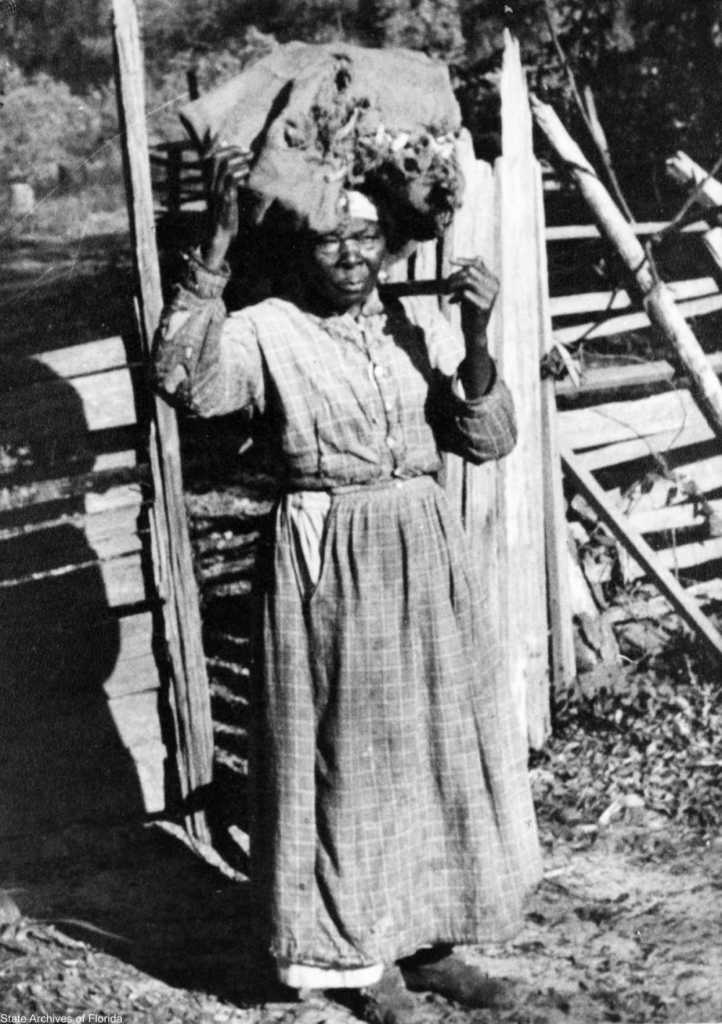

Many enslaved persons were given only a very tiny amount of fabric per year: up to 7 yards of fabric, sometimes less. To make a dress for an average-sized adult woman in 19th century style would have taken around 6 yards, so this is a ridiculously tiny supply. It is possible that the records these facts are based on came from plantations with their own weaving houses and in some cases homespun fabric may have supplemented the clothing fabric on record.

Large and successful plantations would have had a variety of specialized industries going at once: carpentry houses, loom houses, kilns, cookhouses, blacksmithing sheds, various summer kitchens, and more to supply as much as possible without buying it. However, this does not mean that the enslaved had access to yards and yards of extra fabric. The low allotments of fabric are not uncommon in plantation bookkeeping and not all plantations would have had a loom house.

Many enslaved people did not have enough fabric to make a proper outfit from, and the allotment left no extra for repairs, no second outfit, and no Sunday Best. As clothes became damaged and torn, some simply wore the articles until they fell off their bodies, having no way to change the situation. The plain fact is that slave masters and overseers were looking to save as much money as possible, even at the expense of the well-being of the people from which they drew profit.

Better clothing was sometimes used as a tool of manipulation on plantations. The offer of something nice was considered an enticement for the enslaved servants to work harder, which may have been another reason why they were so poorly supplied to begin with. Sometimes overseers would offer the most productive person this week/month a new coat, for example.

A Controversial Solution

For some slave masters another answer seemed logical: let them buy their own clothing. Some enslaved persons were allowed to engage in side linesor cottage industries in order to earn enough money to buy the amount of fabric they would actually need in a year or to buy ready-made clothing if it was available. They might sell handicrafts (like baskets or brooms) or eggs or chickens or produce they grew themselves on a small plot of land “given” for that purpose. Slaves had to try to round out the extraordinarily skimpy allotment of fabric they were given each year by doing even more work.

Sometimes what they made on the side was enough to be able to buy something quite nice for Sunday Best. Of course this angered some whites, who did not like to see enslaved people in clothing as fine as (or finer than) theirs and so “slave codes” or sumptuary laws were passed in some locations. These statues dictated exactly what enslaved people could and could not wear in areas where they would be seen by others (the fields, at market, in town, on the road to church on Sundays and so forth). Some slave codes also made it illegal for enslaved people to buy or sell any goods whatsoever in order to keep them from earning money or buying clothes.

This sad chapter in American history holds many secrets. Rather than the narrative that some enslaved people weren’t treated too poorly, what appears to be autonomy was actually just a penny-pinching tactic by slave masters: if someone on their plantation wanted to work the extra hours on top of their already grueling work load, then so be it.

SKM: below-content placeholderWhizzco for DOT