How One 17th Century English Town Worked to Prevent the Spread of Plague

At the time such measures were not the norm.

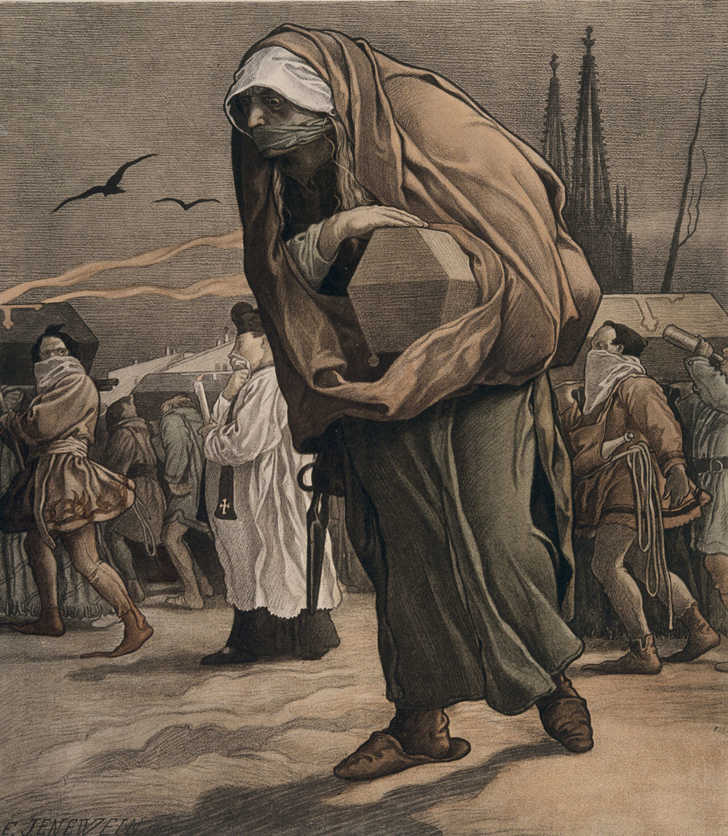

The world was filled with plague that swept across the globe in the 14th-20th centuries. While the bubonic plague was extremely deadly between 1347 and 1351, many other plague outbreaks occurred in the centuries that followed. As the plague, also called the black death, spread in waves from crowded cities to less populated country villages, one 17th English town fought their hardest against the disease which killed millions using a novel apporach.

In the 1660s an outbreak of the plague ravaged London and was eventually spread to the small town of Eyam, in Derbyshire. Since the first European outbreaks 300 years before not much had changed in the way of treatments and medicine. However, one thing had changed and that was the knowledge of just how deadly and easily spread the disease was. For this reason, the people of Eyam took drastic steps to prevent the disease from traveling on to the next town.

The bubonic plague was carried from London where they were having a resurgence of the disease. Bolts of damp cloth that came from London unfortunately carried fleas infected with the bacteria that causes the plague. A tailor’s assistant who was responsible for drying the damp fabric was the first to die of the black death.

At the time in Eyam only about 350 people were living there. When the plague hit the town, around 260 villagers were killed by the disease over a 14-month period. However, to prevent the spread of disease the town Eyam chose to self-quarantine and in doing so undoubtedly saved many lives outside their village.

Only a few months after the first infections, the plague became pneumonic. In today’s terms the disease mutated from a zoonotic illness into a community spread disease that humans could easily give to each other.

In 1666 a local Eyam woman, Elizabeth Hancock, buried 6 of her children and her husband in the span of only 8 days.

One of Eyam’s early deaths was the pastor which left a hole in the town leadership. The replacement rector, William Mompesson, was wildly unpopular with the townspeople. However, he teamed up with the previous replacement rector, Thomas Stanley, a Puritan sympathizer who was living on the outskirts of town after having been shunned by the Anglican Church.

Mompesson believed it his duty to keep the disease from reaching other towns and sought Stanley to help him convince the villagers.

The plan worked, with families that had planned on abandoning their homes staying put at the urging of the two religious leaders. Mompesson also had the support of the Earl of Devonshire, in local Chatsworth, who promised to send food and provisions if the residents would sequester themselves completely.

No one was to be allowed in or out of the village and townspeople left coins in streams of water or in cordon stones. These stones had small divots made in them which were then filled with vinegar before placing the stones inside. These coins were payment for the goods that were left at the border which was a one mile radius around the town.

To further prevent the spread of the plague, church services were conducted outside, with families advised to stand apart from each other in the hopes of stemming the contagion.

There’s no way of knowing how many lives were saved by the Eyam self-quarantine. However, quarantines as we know hem today were not in place for epidemics until the early 1700s, making Eyam a pioneering town. The plague was much less deadly in the 17th century than it had been in centuries previous, in part due to knowledge about the disease and preventative measures undertaken.

SKM: below-content placeholderWhizzco for DOT