The Hoovervilles of the 1930s were the last resort for many folks and thousands of people lived in these shantytowns throughout the decade. After the Stock Market Crash of 1929 increasingly out-of-work numbers of people lost their homes and had no choice but to make do in improvised shelters, sometimes on the outskirts of town, but also in busy downtowns and major metro areas as well.

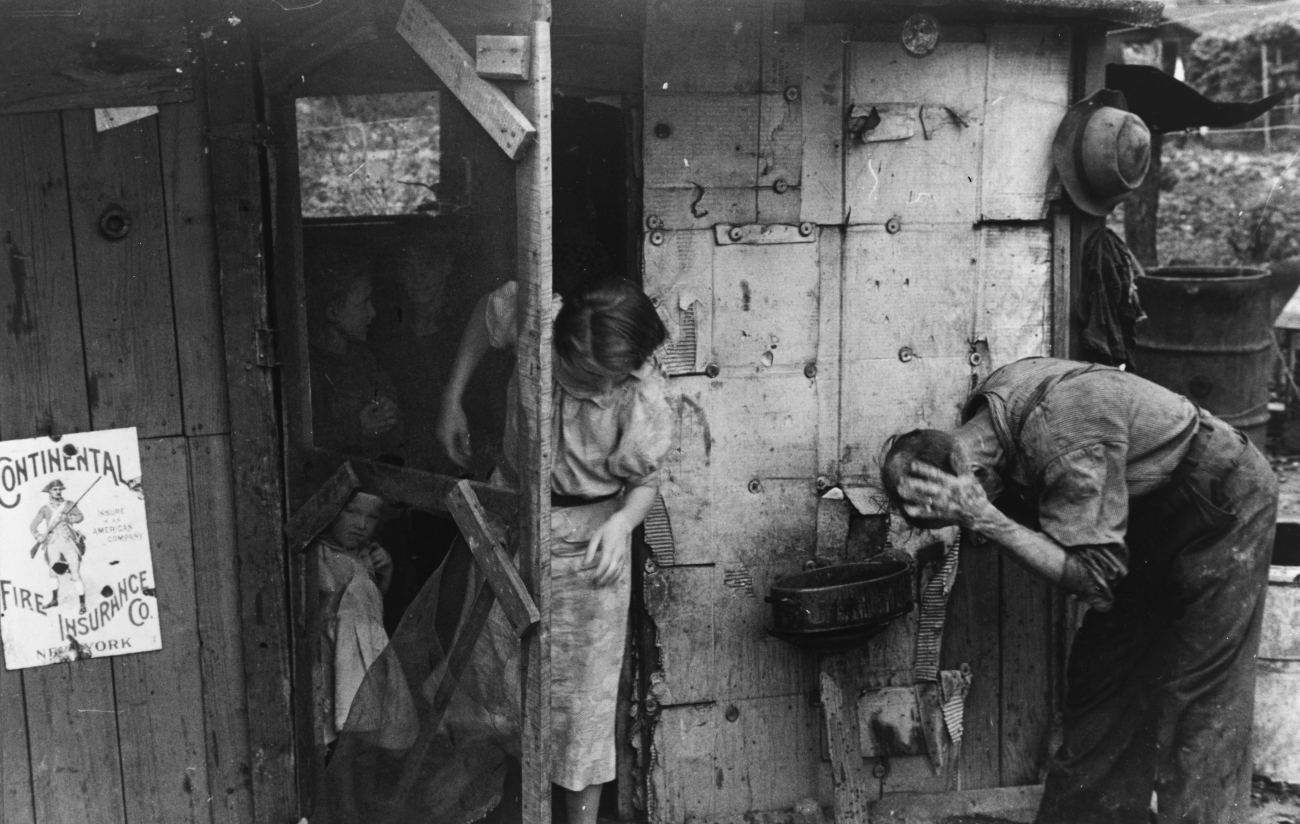

Shacks were cobbled together from old shipping crates, scrap wood, metal roofing, cardboard, and anything else that the residents could get their hands on.

Some of these shacks had tar paper to keep the rain out and even a separate bedroom or some wallpaper salvaged and hastily applied. Other shacks had daylight coming through the cracks and newspaper as insulation.

The name Hooverville came from President Herbert Hoover’s lack of control and help amidst a worsening economic situation. His policies were seen as ineffective and so the worst of the circumstances were named after him: Hoovervilles were shantytowns, Hoover stew was a soup made from whatever you had on hand, and Hoover blankets were newspapers used by the most destitute to keep warm.

With so much animosity it’s no wonder he didn’t win reelection in 1932.

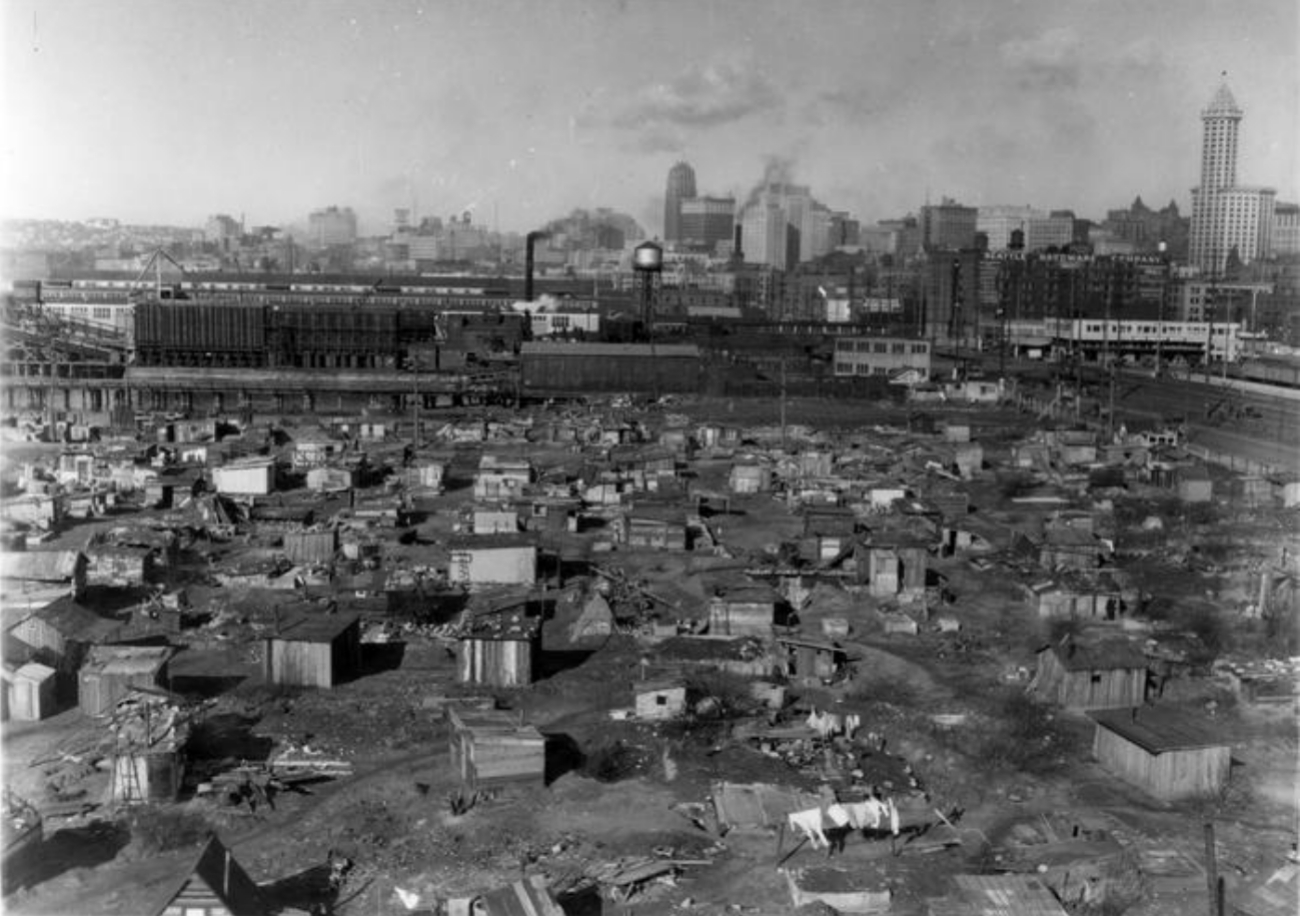

While Hoovervilles looked like rough places, some of them had rules and relationships with the local government. In Seattle a Hooverville sprang up on the tide flats downtown. This area would later be filled in after World War II, but the precarious location was not suitable for most purposes at that time.

Around 1,500 people came to live there, but not without considerable oversight from the local community.

At first the camp was burned to the ground by officials to drive off the squatters. But, when it was quickly repopulated a deal was made. The residents could continue to live there, save for women and children who were expected to live in (presumably) safer housing elsewhere. Basic rules also had to be followed and in exchange they were permitted to stay. Some local businesses even donated food to the Hooverville residents.

Many shanties were built along rivers or waterways for ease of access to water. In Portland, Oregon, a privy was set to float on the Willamette River near a Hooverville in what was a very creative way to deal with the harsh conditions of the squatter’s village.

While the camps were on private land or unoccupied public land, some municipalities simply turned a blind eye to them as there was little other choice for these residents.

Many residents had small stoves inside for cooking and heat, but some were so poor they had to use old tin cans as cups and bowls.

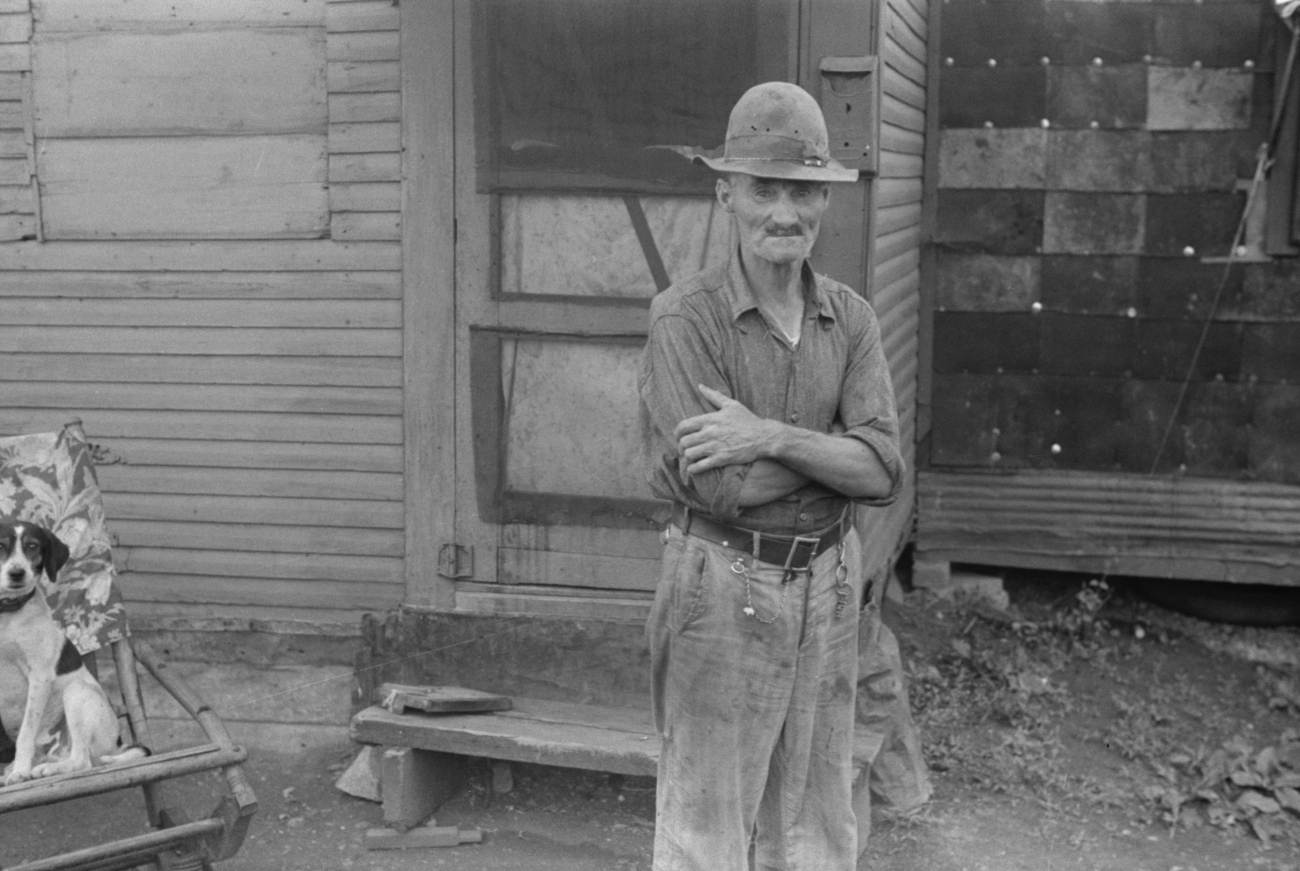

Among the camp residents were hobos and migrant workers, former farmers who had lost everything, and even some middle class workers who found themselves completely without food or employment.

The worst year for Hoovervilles was 1933, as Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration was still two years away. It was in operation from 1935 to 1945 and did much good towards helping many people get back on their feet. But, even into the late 1930s some still lived in shantytowns. Sadly, for those who had been sleeping rough or living in tents a shack was a step up in terms of accommodation.

SKM: below-content placeholderWhizzco for DOT