What Really Happened to the Donner Party?

There’s so much we don’t know about this ill-fated overland trek.

Just the name alone conjures up images of a bleak winter spent in futile hunger, the wagons stopped by the snow and the fate of their lives forever changed. The gruesome details of this event in history are often dramatized, but the grim truth is perhaps even scarier than anything that was made up about this ill-fated wagon train. What we do know is that things went terribly wrong for the 83 members of the Donner Party, however experts remain divided on what exactly happened.

The Trek Begins

It was spring in 1846 and on the advice of author Lansford W. Hastings (who wrote The Emigrants’ Guide to Oregon and California), George Donner directed the wagon train westward.

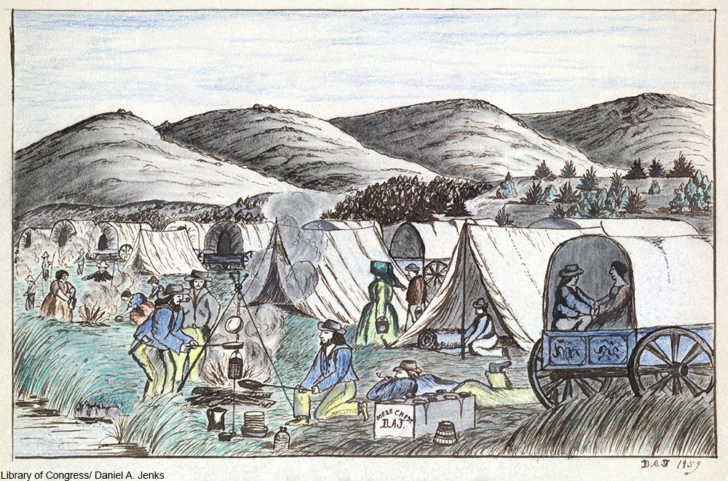

The driving factor was Manifest Destiny, a theory held by most settlers at the time that God had willed the U.S. to be settled and not left to wilderness. This sentiment, along with the promise of free land in the new territories, prompted thousands to make an otherwise unthinkably dangerous trek in good faith that they’d be making a wholesome new life for themselves. However, many families were devastated when they lost members to disease or injury, or lost their supplies or animals in accidents.

The Donner Party followed the book’s advice to use Hastings Cutoff – an ill-advised shortcut of Hastings’ devisingwhich had never actually accommodated a wagon train before. Hastings had written his guide after moving to California himself and seeing the great potential it had, but his proposed route was not the usual way that settlers made it to the California and Oregon.

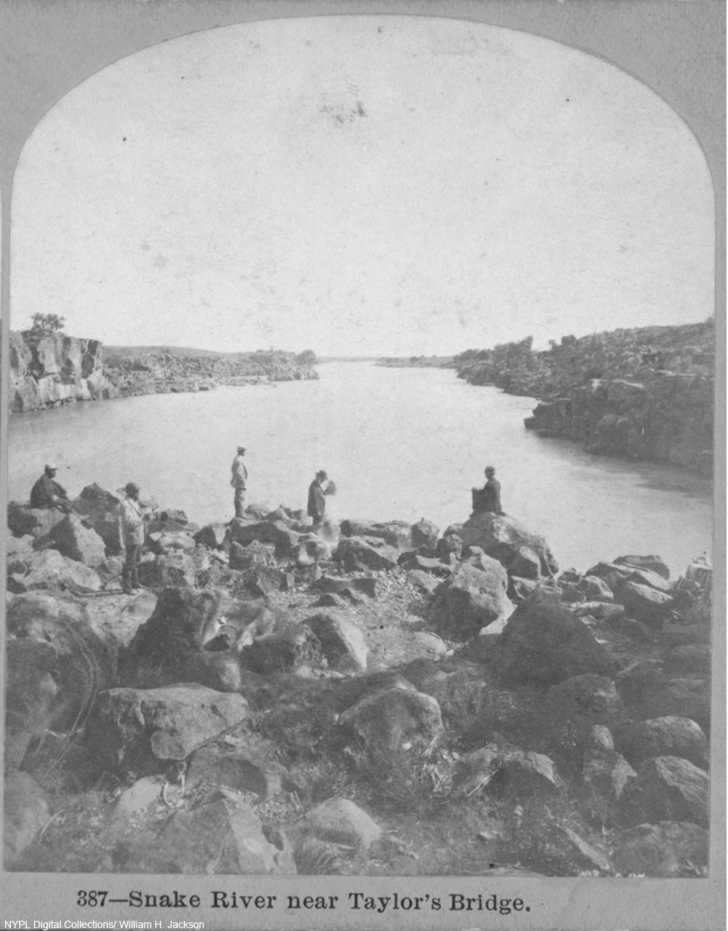

The Oregon Trail, taking wagons past the Snake River Basin, was no easy feat. But, when compared with an untested route, it was at least more reliable. The Donner Party, in taking the shortcut and then being forced to turn back, ended up losing 68 days on Hastings Cutoff. This put them far behind the rest of the people joining the conventional Oregon Trail route. Not only did the Donner Party meet delays, they also left too late. Overland wagon trains needed to leave in April, but the Donner Party didn’t do so until May 12th.

Bad Luck (& Snow) Sets In

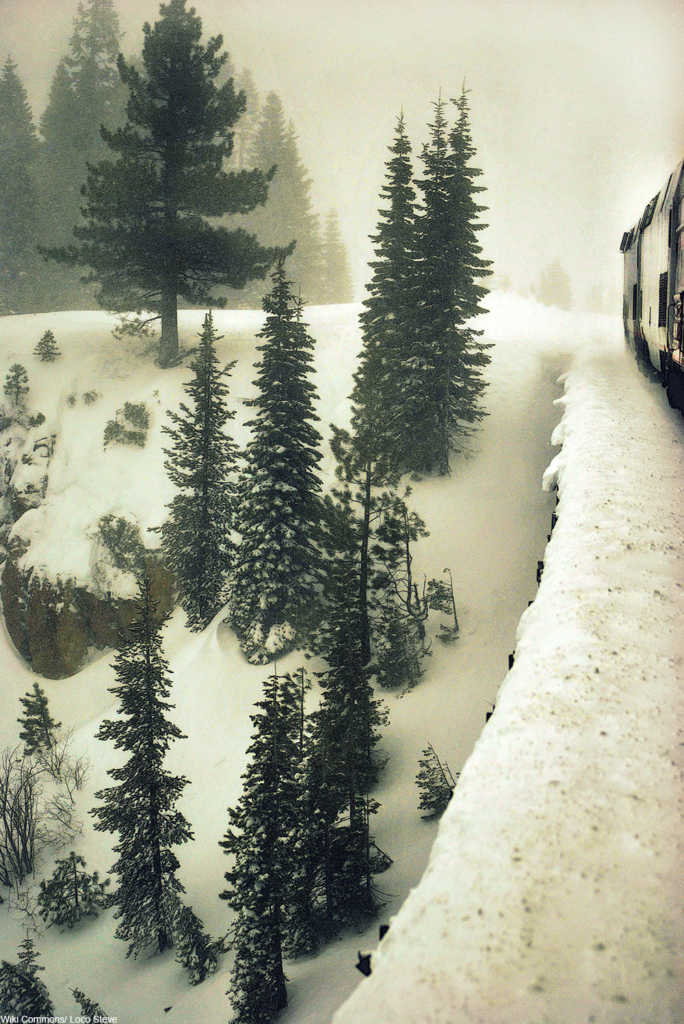

A late start today means diddly compared to what it meant back then. The delay of only a week or two could mean the difference between getting stuck in the snow with no food or being fully set up for winter on a new plot of land. Once the snows hit any distance was pretty much impossible to reach. Settlers needed to be in their new homes by the time winter arrived and the Donner Party delay caused them immeasurable harm.

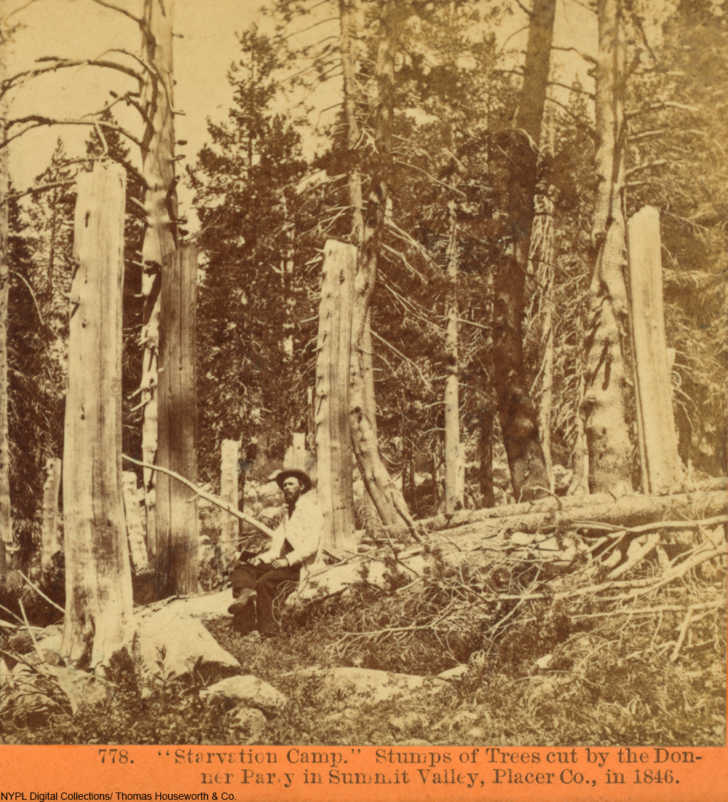

Because they were so far behind schedule when they hit the pass near Truckee Lake (now called Donner Pass and Donner Lake respectively) the snow was already deep and the route impassable. Faced with the onset of an extremely harsh winter, the families did the best they could to set up camp. Makeshift cabins built near hills were anything but cozy and had no doors at all.

Without a supply of food the animals began to starve. Soon the humans would follow suit. The men went hunting for deer with some success, but it was not enough get by on. They ended up eating all the of their animals, including the dogs.

The families split into two groups in their overwinter camps. This meant that there was no longer a unified course of action. According to several different eyewitness accounts, the scene that unfolded was chaotic, full of fear, and led to murder and cannibalism. If true, it was not the first murder of the Donner Party.

James Reed killed a teamster in self-defense near Salt Lake after arguing with him. Despite the fact that the men of the Donner Party would not hear of self-defense, they also could not bear to hang Reed in front of his wife and children so they settled on leaving him in the desert with no food or water to die as punishment.

Amazingly, Reed didn’t die. Rather, he made it to California before the others because his oldest daughter had ridden ahead to leave him food and guns. Reed had even left the Donner Party notes about which ways to avoid. However, this did not keep the group from getting stranded in the mountains of what is today the Tahoe National Park.

Was There Cannibalism?

A Donner party member diary entry by Patrick Breenfrom February of 1848 is chilling: “Thursd. 25th…Mrs Murphy says the wolves are about to dig up the dead bodies at her shanty…Frid 26th froze hard last night to day clear…hungry times in camp, plenty hides but the folks will not eat them we eat them with a tolerable good apetite. Thanks be to Almighty God. Amen Mrs Murphy said here yesterday that thought she would Commence on Milt. & eat him. I dont that she has done so yet, it is distressing. The Donnos told the California folks that they commence to eat the dead people 4 days ago, if they did not succeed that day or next in finding their cattle then under ten or twelve feet of snow & did not know the spot or near it, I suppose they have done so ere this time.”

According to this account, there were those in the camp who were resigned to cannibalism as the months went on, with plans to dig up those who had died. Breen’s account lists the only other food at the camp: hides. Boiled hides will certainly give one something to chew, but they don’t provide the calories and nutrition needed to survive the winter cold in shanties without the necessary supplies.

Of the 81 people who got stuck in the Sierra Nevada mountain pass in November of 1846, only 41 were found alive the next year, scattered throughout the range. Rescue parties had made contact several times, leaving horses behind (which were eaten), but the unusually harsh winter meant that up to 25 feet of snow were dumped on the mountains that year.

According to accounts, the first to be eaten were the bodies of 5 emigrants who had died of hunger and cold. From there, the concept of cannibalism grew to become a viable survival method for many in the group. Of those trapped in the snow, more than half were under age 18, which made procuring food and protecting the children of paramount importance.

According to the final rescue party who arrived in April of 1847, one of the party members (Lewis Keseberg) was supposedly preparing a dish of human organs and when interviewed at the time Keseberg claimed to have consumed parts of Tamsen Donner, wife of George. Keseberg would later be branded by the press as a raving mad cannibal who enjoyed eating human flesh and turned down the fresh food that was offered by the rescue party. In later interviews Keseberg denied killing Tamsen and described how horrible it was to have to eat human flesh, let alone the flesh of a fellow starving person. The media had made him into a monster, something he would never recover from the rest of his life.

There was also the murder of two Native men (Salvadore and Luis) by William Foster. They had been helping the group at their own peril. The pair were reportedly then eaten by the remaining members of the Donner Party. However, in the newspapers Foster was never demonized like Keseberg had been, which shows just how skewed our perspective on this haunting subject can be.

New research of the bones left at Donner Pass has some surprising results. The bones were exhaustively analyzed by archaeologists, but many were crushed or burned. The results showed no human bones were among them. Human bones, when examined closely, do look different to the bones of other animals. Among the confirmed bones were those of deer, rabbits, mice, small game, and cattle. These findings cast doubt on whether cannibalism actually took place at the Donner overwinter camp and whether it was widespread or not. Of note are the assumptions of some rescuers that the party had survived only by eating their compatriots, as accounts of the rescue scenes vary by author.

The study looked at the remains found at the Alder Creek camp, where George Donner and his family stayed. The camp in question held around 20 people at the start of the winter, as opposed to the cabin camp which held the rest.

All of this research still leaves a lot of questions. Was the cannibalism carried out in a separate part of camp? Were the bones carried off by animals? One account was that wolves would eat the dead if the humans didn’t. In light of this research and the hyperbole around this fabled story, it’s hard to say what exactly happened that horrible winter.

SKM: below-content placeholderWhizzco for DOT