Catherine the Great’s Variolation Letter Sold Big at Auction

She was very firm in her stance.

Catherine the Great was a fierce ruler who was fond of art, excess, and all things new. But, she also had a surprising dedication to the health of her subjects which was unusual for the era. At that time many diseases were endemic and anything form dysentery to cholera to smallpox could take one’s life. It was the latter disease hat ravaged Europe during the 18th century with a 30-40% death rate for the unlucky who contracted the disease. Now a letter about smallpox variolation (an early form of inoculation) from the Russian ruler had sold at auction for a staggering sum.

The letter was sold along with a portrait painting of Catherine for ₤951,000 ($1,073,346) at an auction held by MacDougall’s Arts auction house. According to the listing for the lot the items came from a “distinguished private collection” in Russia.

The painting was created by Dmitry Levitsky, a painter and art teacher who in his lifetime never amassed much fortune. He died in meager circumstances, but despite being born before the Empress, outlived her by nearly 3 decades. It is thought that she never personally posed for him, despite him painting 20 portraits of her. Today he is considered one of the great Russian masters of the era.

This portrait shows the Empress wearing a teal sash in silk moire and a russet cape with ermine trim. A slight smile is shown on her face, something many portraits of her lacked.

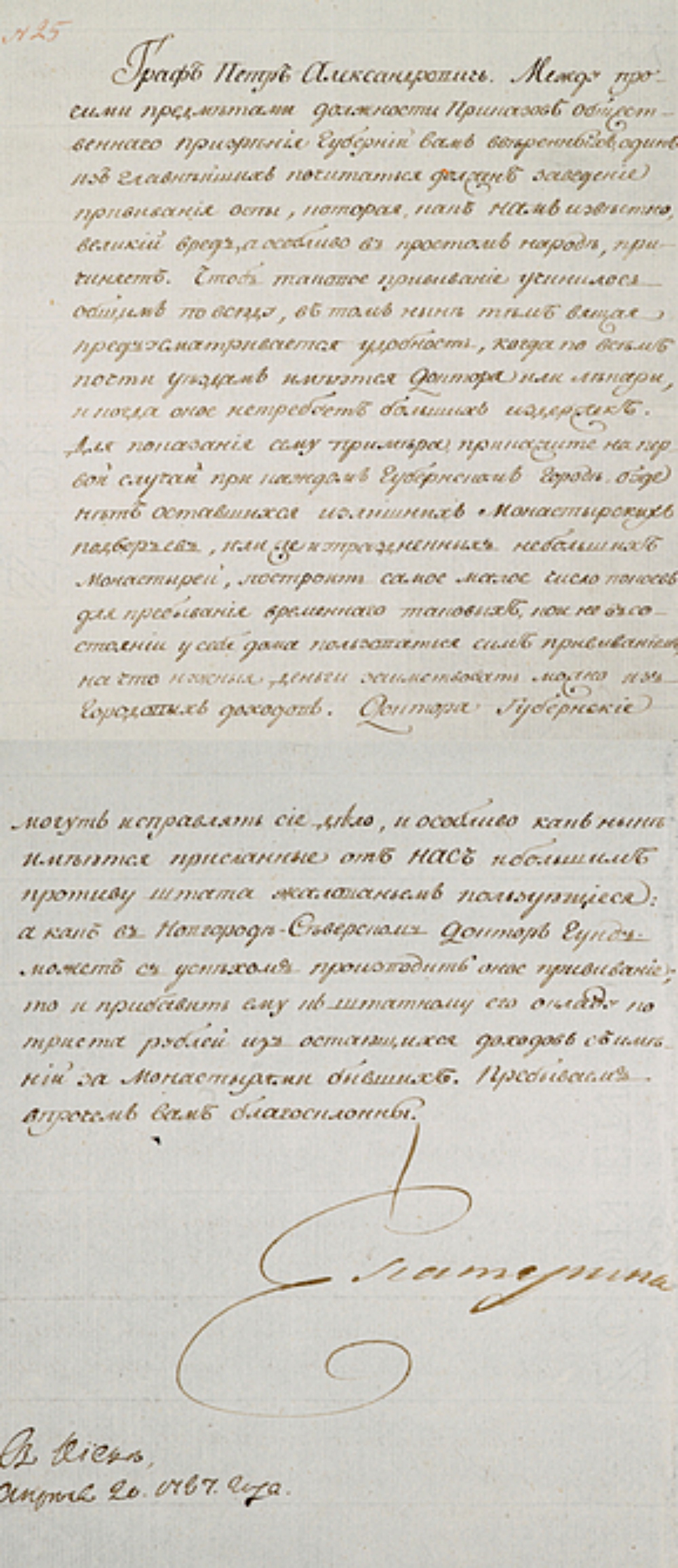

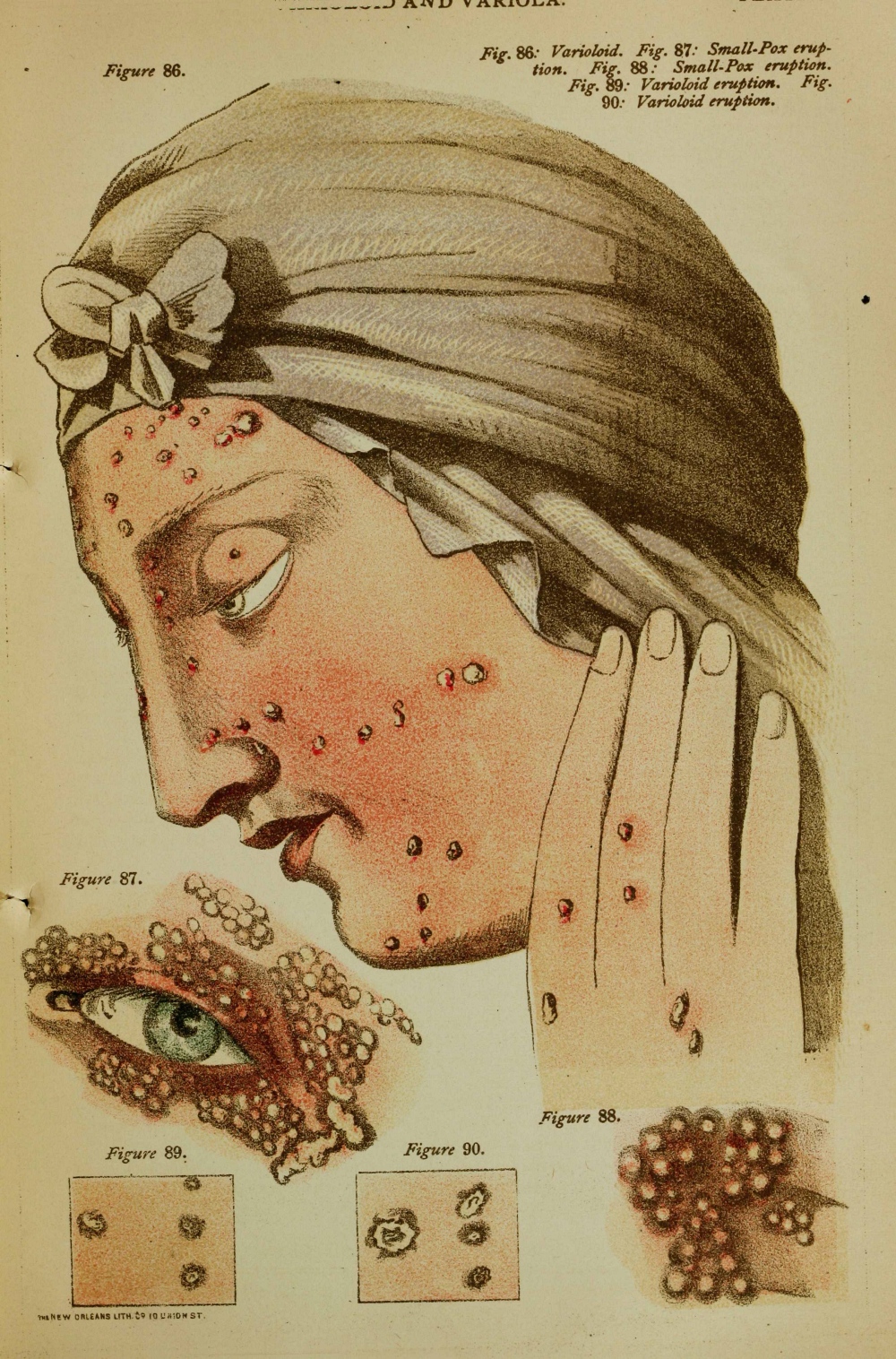

The letter is one in which the Empress discusses the importance of variolation with Count Piotr Aleksandrovich Tolstoy, a general, governor, and diplomat. At the time this method was the most advanced form of inoculation. Patients would have blood or pus from a smallpox-infected person given to them via cuts in their arms. Then ideally the patient would develop a milder form of smallpox. But, some would develop a full blown case of the pox, while others no doubt succumbed to sepsis. It was not a zero-risk procedure and around 2% of the people who were inoculated this way died.

Despite this risk Catherine underwent the procedure herself in 1768 from Dr. Thomas Dimsdale. She made a full recovery and gave him the title of baron that came with a pension. Soon after she wrote to her British ambassador that those who didn’t get the variolation would risk catching the disease the normal way and hence would not be “fashionable”.

The Russian people, however, still feared the procedure and it was shunned. Her letter to Tolstoy in 1787 implored him to use his influence and power to get provincial territories in what is now Ukraine to embrace the variolation techniques in use at the time. She charged that it was, in fact, one of his main duties to do so. She wrote to him that “such inoculation should be common everywhere”.

It was in 1796, the same year that Catherine died, that the British physician, Dr. Edward Jenner, began inoculating test subjects with cowpox (Variolae vaccinae from which we get the word vaccine), a disease that is contained to the skin.

SKM: below-content placeholderWhizzco for DOT