Forgotten Dance Hall Taxi Dancers – A Dime a Dance!

More obscure than the dance crazes it cashed in on these dancers are long gone.

Picture a young soldier with a night of leave and an extra dollar in his pocket. He goes to a dance hall, cutting a rug with the taxi dancers before going off to fight in WWII, taking with him memories of a night of great dancing and no rejected dance offers. Though the trend is rarely discussed these days, back then it was a way of offering everyone an opportunity to dance, of practicing your moves, and of having a good time on the cheap.

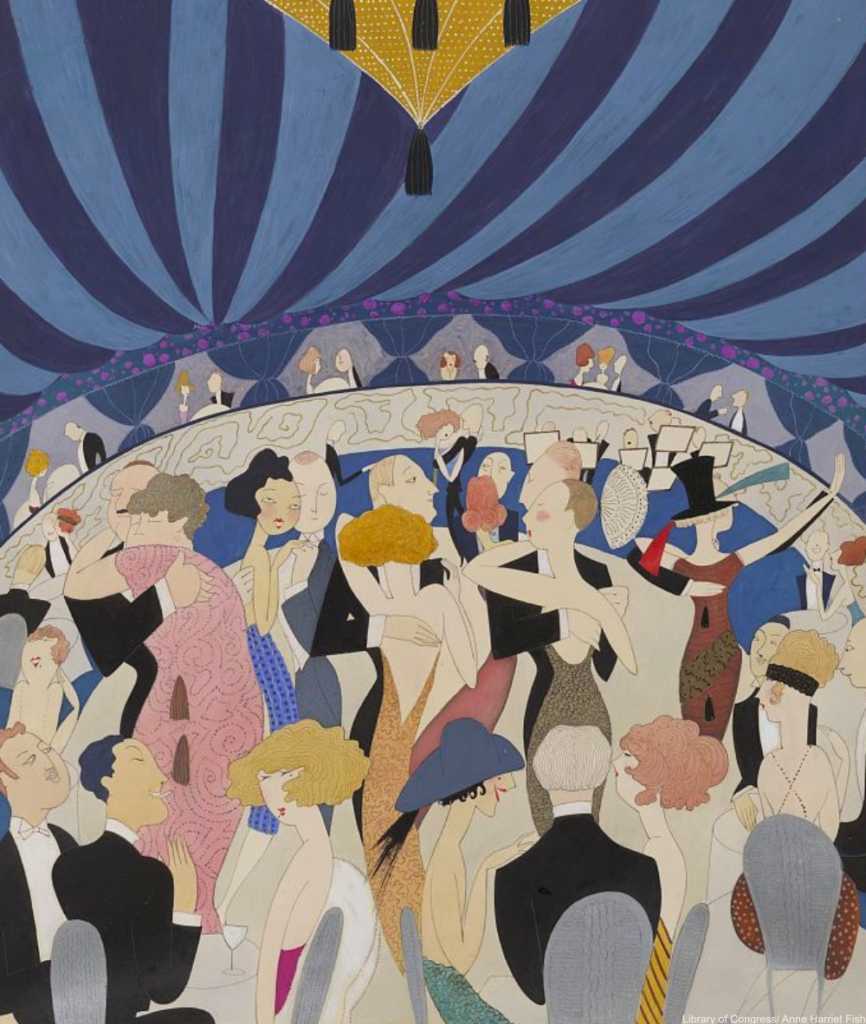

Back when dancing was the backbone of nightlife in every city, dancing was so important that no one could stand to be without a partner for the evening. And few people wanted to venture to a club only to sit by the sidelines on a rare night out. As a response to the many dances being invented and the newly-minted jazz scene, pay-per-dance partners were an ideal solution for many and became very popular in the years between the World Wars.

Anyone could have a dance partner for a fee at dance halls where taxi dancers were employed. Paid dance partners started to appear in dance halls as early as 1913 and often the customer would buy tickets for a dime a piece and then relinquish one ticket each dance to the taxi dancer or dance hostess, as they were also called. The taxi dancer cashed in her tickets to the house at the end of the night and usually received around 5 cents per dance. Some dance halls used a time punch clock for each dance to determine how much of the dancer’s time was spent actually dancing and so figure her rate for the evening.

Taxi dance halls were often well-chaperoned in order to avoid scandalous goings-on between the single young women in the hall’s employ and the droves of men lining up to dance. We can envision this job as arduous for the down-on-her-luck girl or as ideal for a light-hearted chatterbox who loves to dance.

They were sometimes called “dime-a-dance” girls and songs about them conveyed empathy for their perceived plight. Films like Lured (1947) with Lucille Ball depicted at-risk dance hostesses being preyed upon by lecherous men who saw the girls as easy pickings. At the same time, paid dancers were sometimes viewed as money-hungry and seeking illicit after-hours employment. The wonderful taxi dance scene below from Once, Over Light (1931) with George and Gracie Allen gives us another angle: dance hostess as flirty, bawdy, and with an “anything goes” attitude.

Male taxi dancers were also a available. One well-known etiquette guide from 1952 suggests that no woman should be ashamed of employing paid dancers when she is traveling- provided it’s only dancing! Amy Vanderbilt’s New Complete Book of Etiquette advises the following on hiring male taxi dancers: “For unaccompanied women to employ these dancing partners in public places is correct, but for them to put the arrangement on any kind of personal plane is begging for trouble.”

Taxi dance halls continued to be in operation in the U.S. into the ’90s, albeit with a much seedier twist. In modern times the standard payment has been by-the-minute, often with an expected tip at the end. The practice has almost entirely fallen by the wayside in the U.S. as most forms of partner dancing are on the decline. But, in parts of Europe and South America the tradition is still alive and well.

Though taxi dancing has not been a common cultural reference for many decades, it served as key as a key plot device in such films as The Taxi Dancer (1927) with Joan Crawford and Ten Cents a Dance (1931) with Barbara Stanwyck. Whether it seems like good clean fun or an unsavory transaction, there’s no doubt that for previous generations getting to dance was the most crucial part. It was only because of the importance of partner dances like the tango that taxi dancers were required at all, something few people today even know how to do.

Check out some iconic images of how dancing used to be right here!

SKM: below-content placeholderWhizzco for DOT