Think Today’s Health Foods Are a Strictly Modern Trend? Think Again!

Over a century ago “pure food” was the battlecry.

It’s easy to look at the wide variety of health foods in the supermarket today and think about how much simpler grocery shopping used to be. Our current obsession with heath food may seem like a recent development, but there is a movement that goes back to the 19th century which sought to rid us of “adulterated” and “impure” foods.

In the latter half of the 1800s new processing and packaging allowed for a much greater range of foods to be preserved and sold. This was the beginning of the pre-packaged food boom and consumers were led to believe all kinds of things about these new foods. There were few laws in place on how foods were to be labeled or what their ingredients should be.

Watered down products or falsely labeled imitations were considered impure, but testing them was difficult at best. The Pure Food movement sought the regulation of claims, packaging, processing, and ingredients of food and medicine in order make buying pure food a simpler act. Initially linked to the Temperance Movement, concerned with unlabeled alcohol content, the Pure Food Movement can be traced back to the 1870s.

Upton Sinclair’s 1906 book, The Jungle, gave readers a glimpse into what working conditions inside meat processing plants were like. It would be some years before child welfare and work safety laws would address these social issues. But, what many readers came away with was that the conditions in which their food was being processed were not always sanitary. The book fanned the flames of a public movement that had been going strong for decades.

With few packaging or inspection laws, consumers had a hard time telling the difference between the fake or poor quality foods and quality products. Established food producers felt threatened by the new processed and imitation foods being passed off as the real thing, or at the very least, as replacements for the real thing.

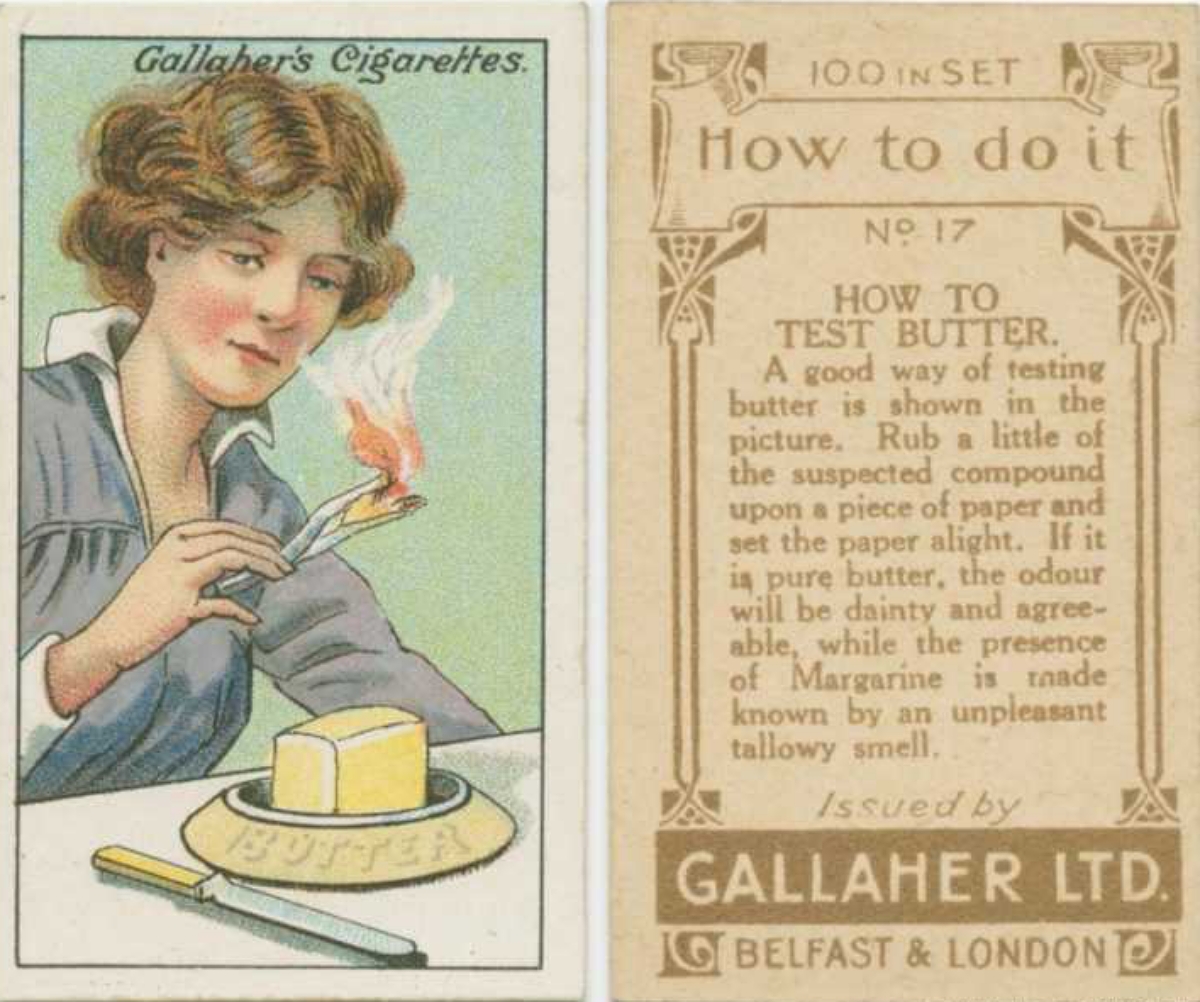

Not only cleanliness, but purity was in question. Even if a food wouldn’t make you sick, was it the real thing? A method for testing if your butter is really butter is shown below. Imagine having to regularly test your food! Before food safety laws, the burden of inspection fell 100% on consumers.

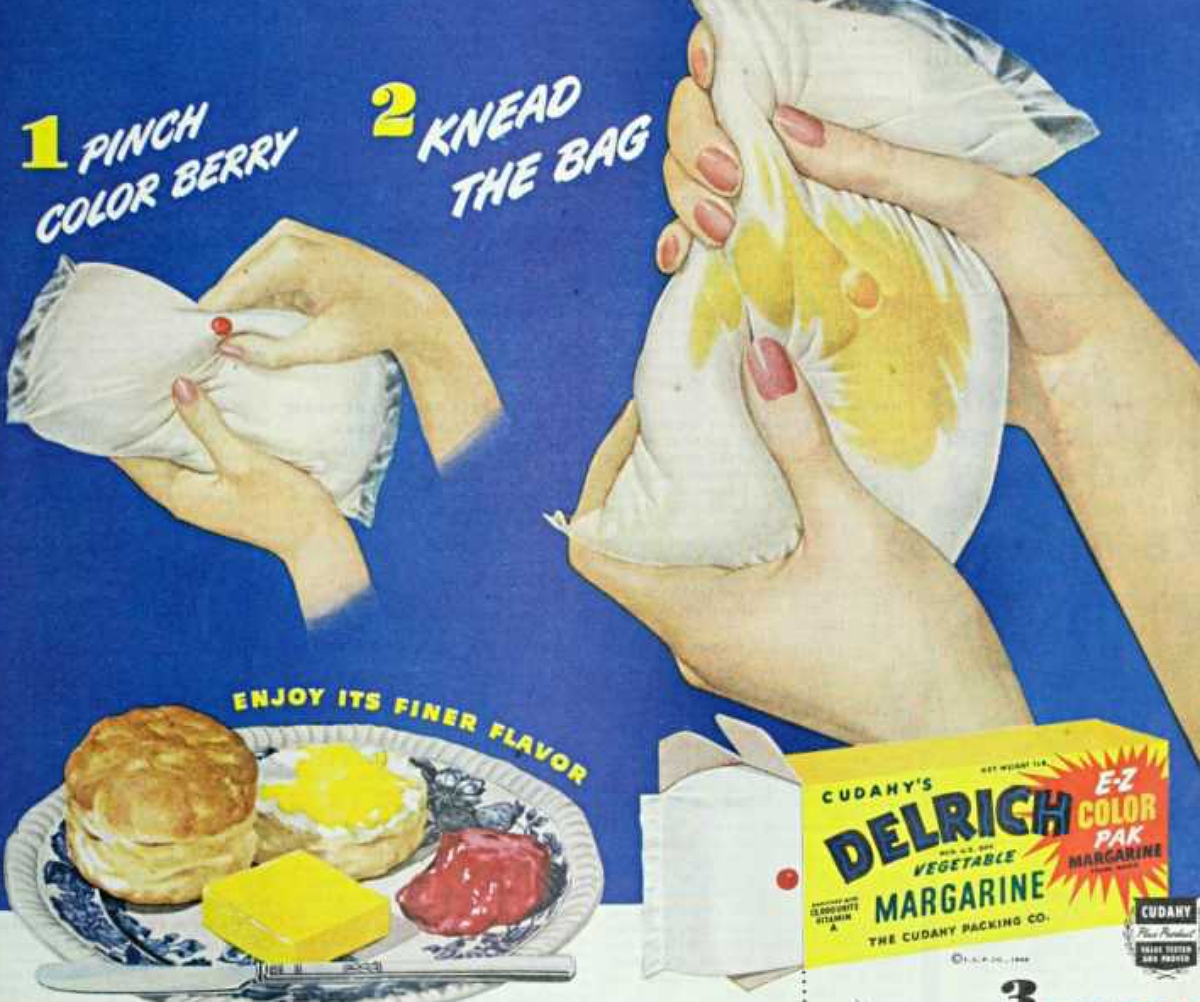

One of the most notable cases was the controversy over margarine. Butter manufacturers wanted to keep margarine from becoming popular, which is why the colorant often came separately and had to be mixed in at home. The idea was that legislation requiring consumers to see margarine as a pasty white substance might deter them from believing that it was butter. And, in some places it was mandated that margarine be dyed bright pink in order to firmly convey that it was not a natural dairy product. Margarine laws remained in effect for many decades and some were only repealed as recently as 1967!

Medicines were also required to have proof of ingredients and effectiveness, ending a booming trade in cure-alls of dubious formulation. Pioneers in the industry of modern chemistry argued that the additives might not be healthy to consume. Harvey Washington Wiley was one such man and he formed the Poison Squad, a group of men dedicated to consuming various poisons and having the effects recorded. Alice Lakey, a consumer activist concerned with the quality of food, invited Wiley to speak at one of her groups. Wiley and Lakey were among 6 people who visited the White House to petition President Theodore Roosevelt to pass laws on food safety in 1905.

The Pure Food and Drug Act was passed in 1906, presided over by the Bureau of Chemistry, of which Wiley had been chief since 1883. This office later became the Food and Drug Administration in 1930 under President Franklin Roosevelt.

The Pure Food and Drug Act was the first step to ensuring that foods were safe to eat and were of known ingredients. Subsequent additions and changes to the structure of the FDA would further manage the labeling and sale of food, drugs, and cosmetics. But, without the concerned citizens of the late 19th century and early 20th century, we would not have the luxury of knowing what’s actually in our food. The idea of having quality, unadulterated foods is not so much a recent trend, but a revival of a basic idea from nearly 140 years ago!

SKM: below-content placeholderWhizzco for DOT