The Murphy bed has a place in popular culture thanks to more than a century of usage. But, it wasn’t as simple as a person who creates a prototype and then goes into production making a product. The Murphy bed has a long evolution that was born of a need for space in rapidly growing American cities, but was also seen as a type of curiosity. So take a look back with us at some of the earliest hideaway beds from the late 19th century and early 20th century and the evolution of the Murphy bed.

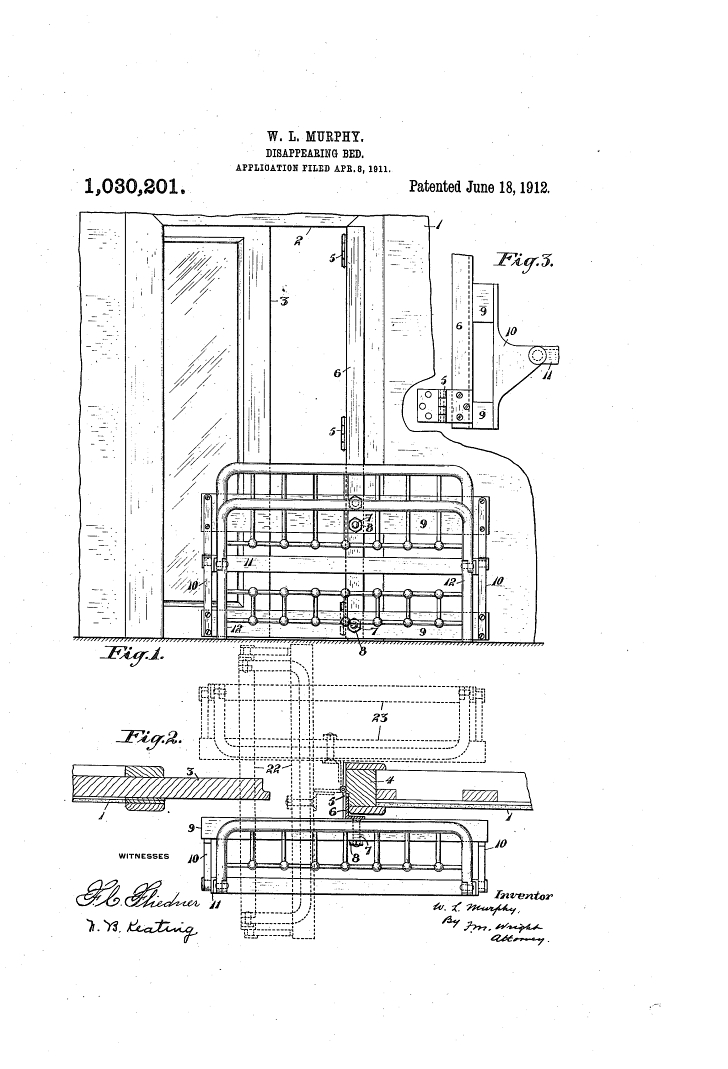

The patent for the first Murphy bed was was filed in 1911 as the “disappearing bed” by William L. Murphy. This innovative design allowed for a room to be converted at dawn from a bedroom to a sitting room by folding the bed back into a chifforobe style cabinet that was mounted to the wall. The name caught on, as did the concept of having convertible furniture that freed up space.

A family legend was that Murphy (who had little money a the time) was smitten with an opera singer, but due to strict moral codes of the era would never expect his intended to be in a bedroom alone with him. And, his solution was to turn his bedsit into a living room by putting his bed away using his new invention, thereby allowing him to get to know her better. The couple wed in 1900.

Whether or not that tale is true what we do know is that in 1900 a burgeoning film industry was already using the Murphy bed as the main plot device for short films. Subub Surprises the Burglar (1903) is remake of a film from 1900. In this film a man sleeping in a Murphy bed is burglarized, at which point he flips himself into his bed which is kitted out with guns on the bottom, turning his closet-cum-bed into both shield and artillery. You can watch the film below.

So were these beds already being made by Murphy before he submitted his patent? It’s possible, but the truth is that hideway beds had actually already been around for decades by the time Murphy created his design. The reason for this could be that not everyone who created convertible beds had a patent on their design.

Little is known about the Higgins bed, but it looks very much like the classic Murphy bed. Except the Brooklyn Museum places the photograph of this piece of furniture at around 1870! This “Parlor Cabinet/Bed” looks just like we’d expect a bed like this to- having grown up with the notion of Murphy beds. But, not all of them were recognizable to us today as hideway beds.

The Brooklyn Museum also has in their collection a convertible piano bed from 1885! This piece could be placed in the family’s parlor and by day the room would look stylish and functional as not everyone could even afford a piano. Then by night it was a bed, affording a large family more flexibility with their sleeping arrangements. Later Murphy beds catered to the poor, but early versions may have appealed to middle and upper classes as curiosities.

We do have some questions, like does the piano play? Does it play well? Does it make noise if one tosses and turns in the night? What about *ahem* other nighttime activities? Sadly the only video of this piece in action has no sound so we’ll probably never know.

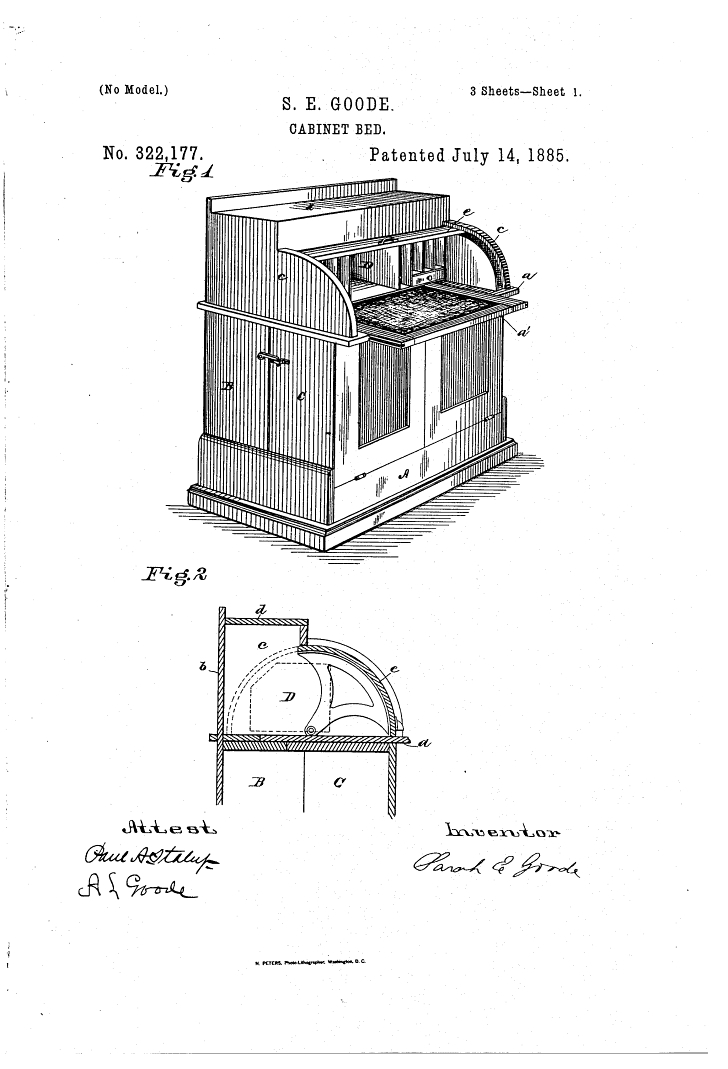

Also in 1885 a patent was filed for a “cabinet bed”. Sarah Goode (née Jacobs) was born into slavery around 1855 and married a man whose occupation was as a stair maker and carpenter. The pair later opened a furniture store in Chicago where legend has it that Goode’s customers complained that they like the furniture but simply didn’t have anywhere to put it in their small, urban homes.

Unlike Murphy beds or piano beds, Goode’s cabinet bed was movable and short in stature, allowing for a safer experience and ease in moving the bed around the room. Upright hideaway beds need to be fixed to the wall so that they do not topple over, but cabinet beds could be freestanding.

Another feature that separated Goode’s design from all but the piano (if it played) was that her roll-top cabinet desk-bed was actually functional as a desk, with working storage and a writing surface to be accessed when not in bed form. It is unknown if Goode’s furniture company then made these beds or if the patent was licensed to other furniture makers. But, an extant example of cabinet-desk-bed from the era does not bear any mention of Goode or her patent, instead bearing the label of A.H. Andrews & Co, based in Chicago, that claim to be the “sole manufacturers” of such a device.

Goode was one of the first African American women to ever hold a US patent, but little is known about her life. She is believed to have passed away in 1905.

Today both new and antique Murphy beds are quite costly, with around $1,200-1,500 being the cheapest price in most areas for either (though custom built Murphy beds can cost many times that). Many of the older Murphy beds were made in the Eastlake style, a paired down take on late Victorian carved furniture.

Immortalized as the comedic device in films and other media for many years, the Murphy bed (as all convertible beds have come to be known) holds a special place in American culture. But, in the early 20th century these furniture pieces provided space to the working classes who couldn’t afford large apartments in densely-packed city spaces. They became the most functional option for those living in one room tenements or other small dwellings. Whether you have a need for space or are simply enamored with the novelty of the concept, Murphy beds continue to be a fascinating type of furniture today.

SKM: below-content placeholderWhizzco for DOT