The “Tiffany Girls” Responsible for Those Gorgeous Lamps

They were the unsung heroes of lamp-making.

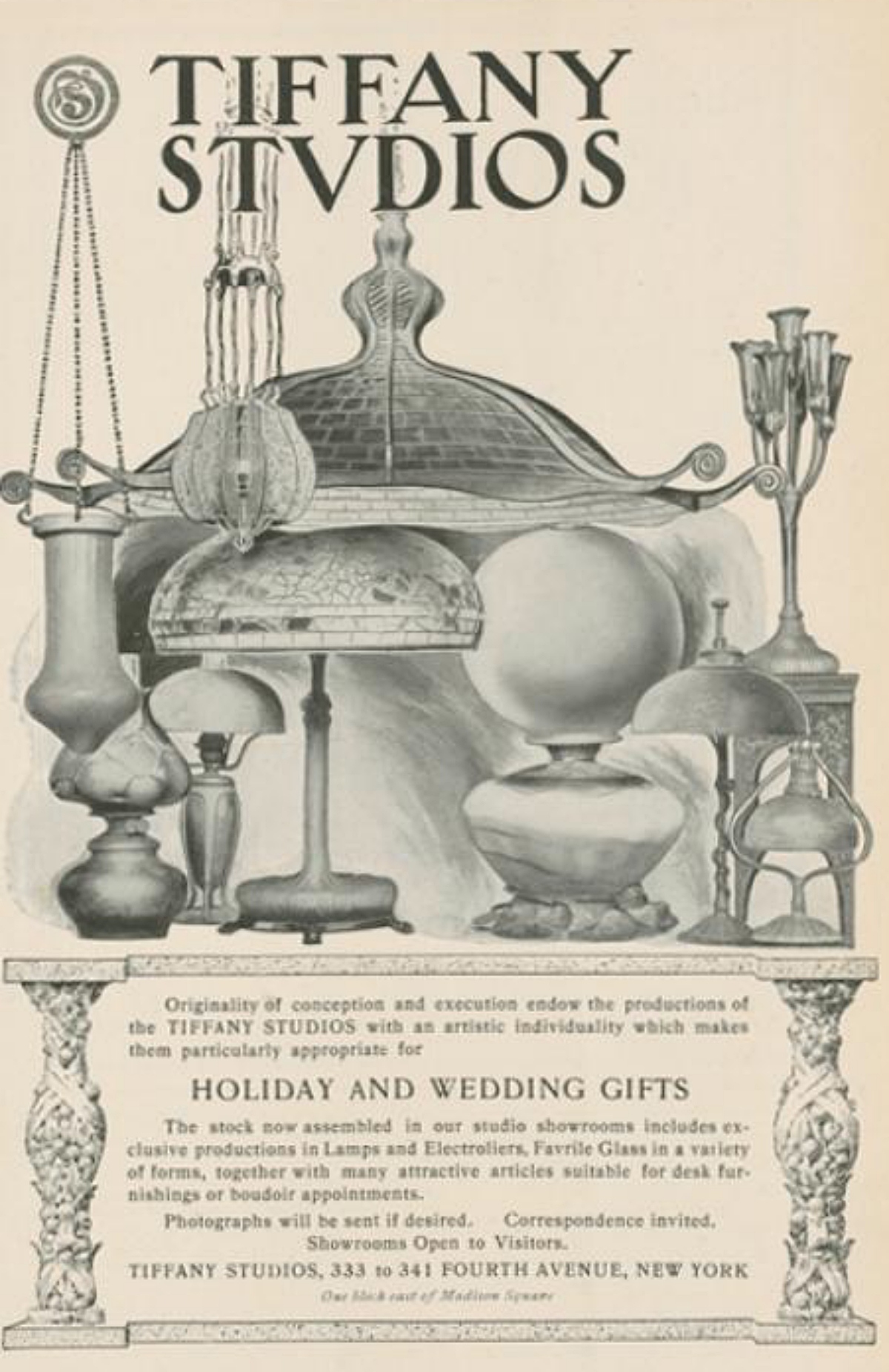

The name Tiffany in relation to lamps today can refer to any style of stained glass lamp. But, the real deal was on a whole other level. It could take thousands of tiny pieces of glass to create just one lampshade in the spectacular style that Louis Comfort Tiffany pioneered. His team of female workers were publicly unsung yet had their own department, much to the chagrin of their male coworkers.

Tiffany had significant talent and creativity, but had a step up in life thanks to his father’s booming silver and jewelry business. The younger Tiffany set out to create pieces of furniture, home decor, and glass that far surpassed anything on the market at the time in terms of quality and design.

With a combination of forward design from the Art Nouveau movement and the finest in materials, each piece was itself a work of art. However, despite the many hours each piece took to create, individual artists within the organization were not often credited and this was especially true when it came to the head of the women’s glass cutting department.

The so-called Tiffany Girls were led by Clara Wolcott Driscoll, once a student at the Cleveland Institute of Art and the Metropolitan Museum Art School who was esteemed by Tiffany himself. However her male coworkers at one point threatened to quit if she didn’t step down in 1903.

Tiffany wasn’t having any of it since she was one of his primary designers whom he took to Europe for inspiration trips to enhance their designs.

Despite the fact that she was not publicly acknowledged for her work she was the originator of around 30 of Tiffany’s lamps, including the most recognizable of them all: the dragonfly lamp and the wisteria lamp.

Driscoll and her younger sister, Josephine, both went to work for Tiffany Studios in 1888. The older sister was pushed out of her job in 1900 when she married.

She returned in 1902 after she was widowed. When she married again in 1909 she lost her job because it was considered unfair to employ married women as their husbands could provide for them. Prohibiting married women from employment freed up a “family wage” for a man. Such practices were common at the time and were in no way illegal.

In 2005, 61 years after Driscoll’s death and 41 years after the 1964 Civil Rights Act, historians unearthed letters between the artist and her family revealing her important role in the creation some of the most iconic Tiffany lamps.

Since then she has been the subject of both an exhibition of her work in Cleveland and a book (A New Light on Tiffany: Clara Driscoll), with the long-concealed story of the head Tiffany Girl revealing just how much women actually contributed to American design.

SKM: below-content placeholderWhizzco for DOT