Rare Black Death Mass Grave Sheds Light on How People Handled the Outbreak

The site had yielded a wealth of information.

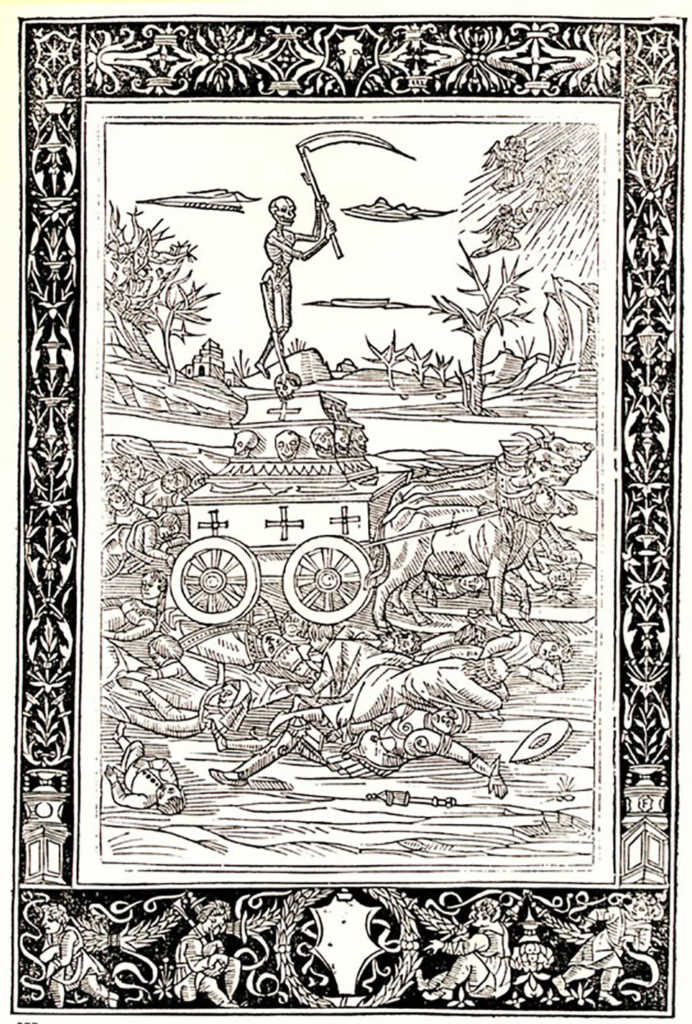

Between 1346 and 1353 the Black Death ravaged Europe, killing as many as 200 million people. Records at the time were not always kept, so it’s hard to say for sure how many people fell victim to the disease. Even many records of churches, graveyards, and doctors were either abandoned in the chaos or lost over time. However, a rare mass grave of Black Death victims has recently been uncovered in England and it is shedding a lot of light on how the disease was handled in the 14th century.

In Lincolnshire county in the East Midlands of England, a mass grave from the era containing the remains of 48 individualshas been found by archaeologists.

The area was first uncovered in 2011 as part of a program of the University of Sheffield to discover more about the Thornton Abbey site, a medieval church and grounds which contained a cloister and hospital. The gravesite area had since been used for sheep grazing for hundreds of years, but underneath the top layers of dirt researchers uncovered the mass burial site in 2015. Now, detailed analysis of the skeletons has revealed a lot about who they were and how they died.

The site contains the skeletons of men, women, and children, with the latter group making up the majority of the skeletons on the site. The mass burial suggests that the population living near the gravesite in the 1300s was unable to deal with all the bodies from the plague and had to resort to burying the dead in an uncustomary way.

The mass grave has several layers, which suggests that the bodies were buried over the course of days or weeks. This makes a lot of sense when you consider that about half of England’s population died from the bubonic plague in only a few short years. The devastating disease was lethal for most people who were unlucky enough to catch it. With bodies piling up quickly they had to be buried in the most efficient manner.

Whatever the exact reason for the mass burial and the presence of so many children in the grave, analysis of DNA from tooth samples of the skeletons has confirmed the presence of Yersinia pestis, the bacteria responsible for the Black Plague. This bacteria has only been confirmed in two other burial site from the mid-1300s.

According to church records the bubonic plague hit Lincolnshire in 1349, which lines up with coins and other artifacts found in the gravesite that date from the mid-1300s.

One such object is a Tau cross (above), a charm made from gold which was worn around the neck to ward off St. Anthony’s fire. This would have been considered medical care at the time.

The gravesite is the first of its kind ever discovered outside densely-packed cities, showing just how much the plague affected even communities far removed from metropolitan areas.

Normally the dead would have been buried in a churchyard, but the location of the mass grave so far from the church

indicates just how dire the situation was. Hugh Willmott, leader of the dig, has stated that if the priest or gravedigger had succumbed to the Black Death, standard protocols for burying the dead might have been completely abandoned.

You can see more of the archaeological process in the University of Sheffield video below from back in 2016, a year after the mass grave discovery.

SKM: below-content placeholderWhizzco for DOT