The Time New Yorkers Rioted in the Streets Over Grave Robbing

It was one of many such angry mobs at the time.

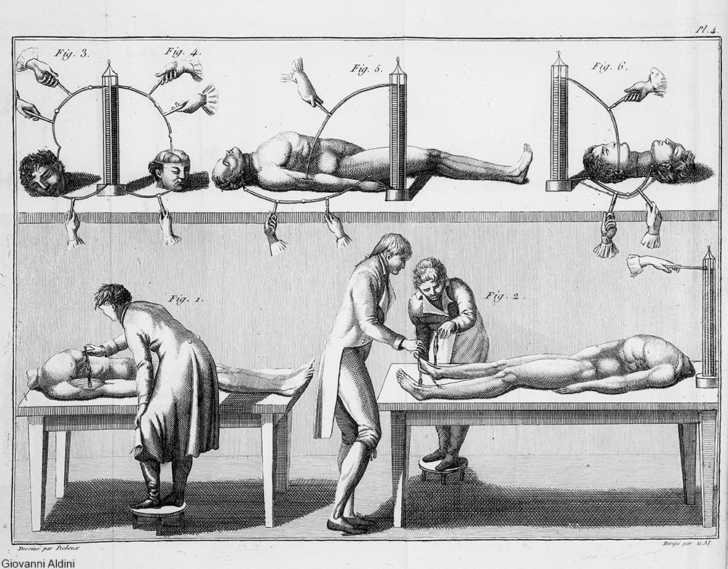

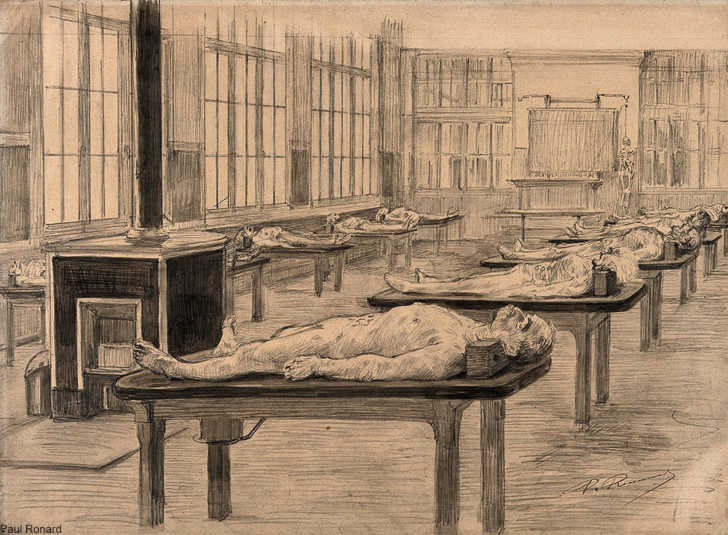

In Europe, the fear of being buried alive was well-documented. Well into the 1800s concerns over grave robbing were widespread. Devices to prevent premature burial, grave robbing, and even controlled access to graves were all common tactics in the 1700s and 1800s. Similar fears over so-called “resurrection men” robbing graves of their corpses was rife at the time. The burgeoning medical field used corpses (many times illegally) to discover the human body in detail. It was the dawn of a new era of science, but many regular people were horrified to learn that dissections at medical schools were often done on stolen bodies. What’s worse is that a school in New York in the 1780s was reportedly using dead bodies from the pauper’s cemetery, preying upon the unmarked graves of those who could not afford a proper burial and whose families could not fund a legal battle.

At the time, bodies were a hard-to-procure commodity because there was no such thing as donating one’s body to science. It was quite the opposite in that the taboos surrounding death and burial meant that it was considered shocking and an indignity to the dead to deface a corpse in any way.

Thefts of bodies often occurred in the cooler months, as preserving bodies was not yet a known feat. In Scotland, the rise of body snatchers would give way to the murderers, Burke and Hare, who did not wait for their victims to pass away naturally before selling the bodies to the university in Edinburgh. However, the stealing of bodies had been going on for decades by that point, in Europe and in the U.S.

There was no satisfying the need for cadavers to use in teaching as surgery and anatomy students depended on first hand experience with dissection in order to learn the human body.

The Pauper Cemetery and what was then known as the Negroes Burying Ground, both in Manhattan, were filled with the bodies of those who could not afford elaborate burials, often placed 2 or 3 to a grave plot.

Both of these cemeteries were close to Columbia University (then known as King’s College), which had been offering classes in the medical field since the creation of the College of Physicians and Surgeons in 1767.

It was in 1788 that a medical student by the name of John Hicks was involved in a scuffle with some local children according to hearsay. Hicks had studied under Richard Bayley who in turn had studied in England where body snatching was common.

Hicks reportedly threatened some kids playing nearby Bayley’s lab, threatening them with the severed arm of a cadaver and claiming it was belonged to one boy’s dead mother. When the child told his father what had happened, they dug up the recent grave and found it to be empty, prompting incredible rage at the disrespect of the whole situation.

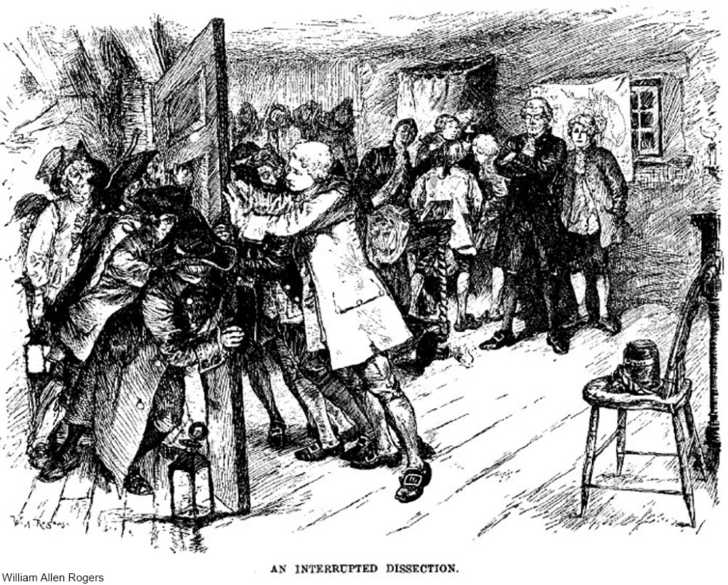

On April 13th, 1788, the man avenged his wife by gathering together a posse to storm Columbia and the nearby New York Hospital, where dissections also took place. Another version of the story tells of a the discovery of a child dissection, which led to a response of outrage from the public.

The anger was centered on doctors and medical students, who were seen as taking advantage of the recently bereaved for their own gains. The mob was made up of working class men and free African Americans, the two groups most affected by body snatching.

An estimated mob of 2,000 angry rioters destroyed the labs and homes of the doctors, and in a gruesome twist even destroyed the remaining cadavers.

The doctors at risk had been shuttled to the local jail for protection – where the crowd soon followed. The militia was called in to quell the violence, but ended up killing some of the mob. Reports vary on how many rioters were killed. Some say it was 5, some say 7, and some think as many 20 may have been killed in all.

This was one of many resurrectionist riots that took place in the U.S. between the Revolutionary War and the Civil War.

The violence and mayhem was contained after a few days of martial law, but public suspicion of medical cadaver usage remained for years afterwards. One year later, a statute was enacted that made it a crime to use “abandoned” bodies for medical purposes. However, the use of corpses from executed criminals were now legally fair game, a tradition inherited from English laws and the Murder Act of 1752.

SKM: below-content placeholderWhizzco for DOT