The 18th Century Secret Society Obsessed with…Pugs?

These cute little dogs were political symbols in the 1700s.

Today Freemasons are known for their work raising funds for hospitals and orphanages, as well their distinctive tiny cars and fez hats on display during parades. We’d never think of the pug as one of their symbols, but in the 18th century a curious society sprung up which modeled itself on the Freemasons and which held as their esteemed mascot the mighty pug.

A History of Freemasons

The earliest mention of the Freemasons dates back to 1390in a poem which was copied from an earlier work. While Freemasons are thought to have originated from a group of stoneworkers in the Middle Ages, not a lot is known about the formation of the group. What we do know is that the spread of Freemasonry gained steam in the 1700s after four smaller lodges combined forces to create the Grand Lodge of England. The order had a boon of new applicants throughout the 18th century and across the world.

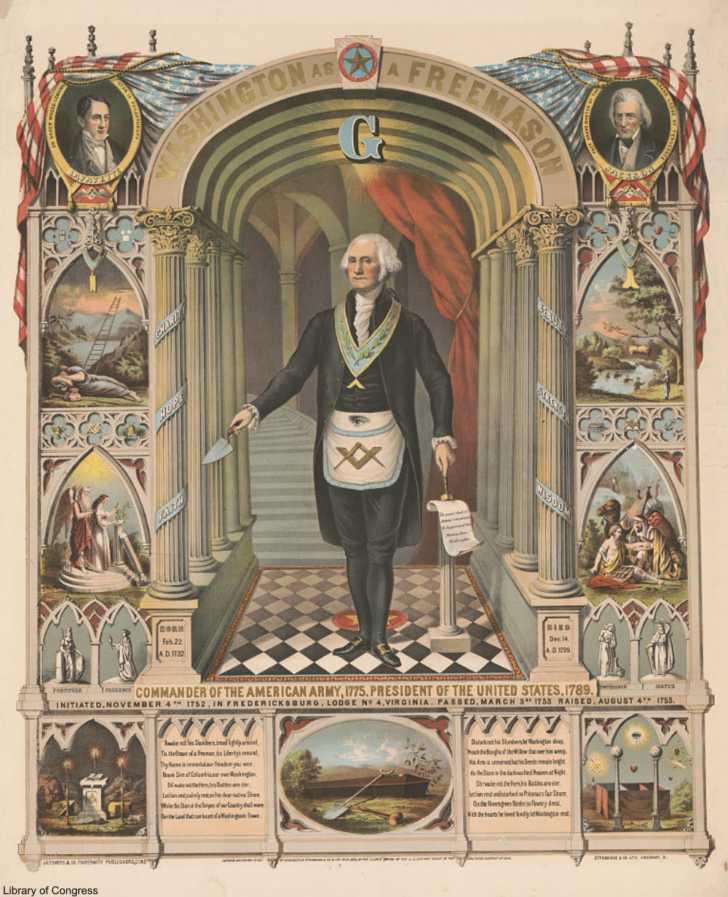

Famous American Freemasons of the 18th century included not only George Washington, but also 20 other signers of the Declaration of Independence. Members of this secretive club were known to favor independent governance and gained a reputation for conspiring against royal powers. Perhaps this is why in 1738, Pope Clemens XII issued a statement forbidding any Catholic from joining in or associating with any type of Freemason.

Creation of a New Order

Not only did the Catholic church highly benefit from monarchies, which many Freemasons opposed, the papacy saw Freemasonry as a denier of the Church. The fact that many German Catholics were members up to that point did nothing to dissuade official papal opinions on the matter. An organization which aimed to help people without regard to religion and to better society outside of (and perhaps above) the church setting was seen as highly dangerous.

Enter a new secret order, highly associated with the Freemasons, which sprung up in Germany beginning in 1740 at the organization of Clemens August of Bavaria. Called the “Mops-Orden” (or Order of the Pugs in German), this group admitted both men and women (provided they were Catholic) and held as their symbol one of the least intimidating animals of all time: the pug.

The pug was seen at the time as a covert and subversive representation of the English Revolution as the breed was a favored companion of King William III, revolutionary king of England from 1689-1702. Owning a pug in Europe was a slight nod in the direction of liberty and rational thought. Not only did the pug have political cache at the time, the dog was chosen as the symbol of the Mops-Orden because of the breed’s unquestioning loyalty, something they expected of their members.

New initiates to the orderhad to wear a dog collar, imitate a pug’s cry, and scratch at the door to get in, as well kiss a porcelain pug statue’s rump to express their unwavering devotion to the order. Members wore silver pug charms and kept trinkets of the breed as signs of their inclusion in the order.

The society flourished until they were outed in print in 1845 in the book “L’ordre des Franc-Maçons trahi et le Secret des Mopses révélé” and disbanded at the Göttingen University at which point they were supposedly shut down. However, there were reports of the society still being active as late as 1902. Famous members of the Mops-Orden included several German princes and the Duke of Bavaria.

The Catholic church has continued its opposition to any type of Freemasonry ever since Pope Clemens XII, though modern proclamations have often dropped the word “Freemasons” and instead has referred to “societies that plot against the church.”

SKM: below-content placeholderWhizzco for DOT