The Dos and Don’ts of Victorian Letter Writing

Everything from paper to the date and the ink was scrutinized back then.

In the 19th century letters were the main form of communication and so were seen as extremely important to get “right” by the standards of the day. This was particularly true for the upper classes and the rising middle class, as they felt that maintaining standards in correspondence was crucial to maintaining the class divide (for lords and ladies) or for climbing the social ladder (for middle class folks). What language you used, how you signed your correspondence, and even how you sealed the envelope were all considered crucial aspects to make perfect before sending the letter in the mail or having your footman deliver it. Read on to find out some of the critical dos and don’ts of Victorian letter writing.

The Baddies of Letter Writing

Not only was perfection in grammar and punctuation non-negotiable, it was also incredibly important to spell everything correctly. In the Middle Ages English was not yet a standardized language and even scholars varied wildly on how to spell common words. To be able to write and to have the time and resources to do so was in itself a privilege and the exact spelling mattered little as long as people knew what you were talking about. This kind of thinking persisted into the 1700s, but by the Victoria era many of the words we know today had agreed-upon spellings.

To misspell a word was to show that either you had a formal education and simply didn’t absorb your lessons or that you didn’t have a tutor or proper schooling. Those with increasing fortunes, like merchants for example, would have had to make sure that every word was correct when writing to their social superiors or else risk being cast out of their social or business circles.

For this reason it was advised to always keep a dictionary close by when writing letters and to look up anything one was unsure about. Arthur Wentworth Hamilton Eaton, author of the 1890 letter etiquette book, Letter-writing: Its Ethics and Etiquette; With Remarks on the Proper Use of Monograms, Crests and Seals, went so far as to state that, “Bad spelling like bad grammar, is an offence [sic] against society.”

Choice Paper

At the time white and cream were the only truly acceptable colors for one to write their letters on. Today we have every kind of stationary imaginable, but even plainly colored paper in the Victorian era was a no-no. The big exception to this rule was that those in mourning should use black-edged paper for their letters so that everyone would quickly know that they had recently lost someone. The width of the black border would indicate the closeness of the person lost, i.e. a thicker line would be used for the loss of a spouse than for a cousin.

Via: William Leroy/ Library of Congress

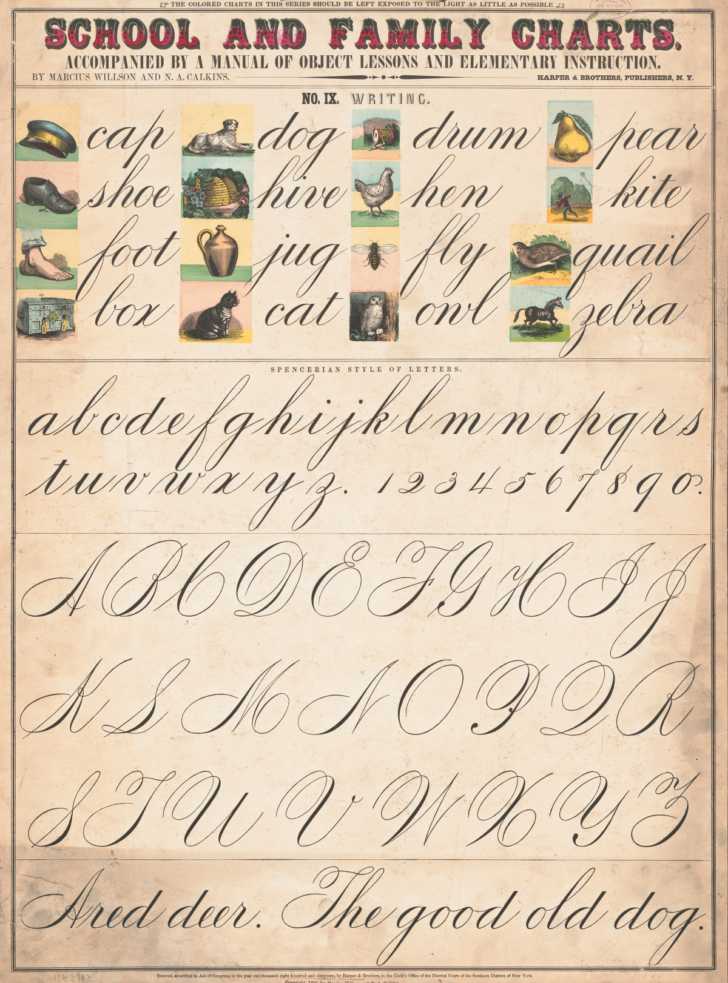

Likewise lined paper was also taboo and was considered “bad form”. At the time you were expected to have learned how to write straight and even without the use of lines during your education. To use lined paper showed that you again either hadn’t valued your education or simply never had one.

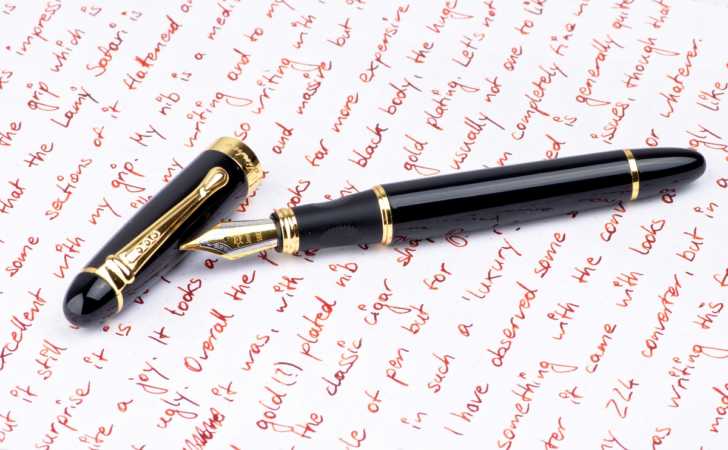

Inky Dink Doo

Black ink was the only acceptable color to write one’s letter in and only the finest quality ink should be used. Cheap ink that faded quickly was considered very disagreeable and showed a lack of concern for the recipient. This was also a problem since people kept letters for years as proof of intent to marry, proof of someone’s intent to inherit, and for many other matters of import in business and personal life. To use fading ink might imply that you didn’t intend to honor your commitments. Using any color of ink besides black was also considered to be in very bad taste.

Via: Marek Kubica/ Flickr

Be Bold, But Not Too Bold

Fine or small handwriting was considered acceptable in business matters, but for personal writing one was expected to create and maintain bolder penmanship with elements that were pleasing to the reader’s eye. However, fancy capital letters, curly cues, or other embellishments were seen as too over-the-top and were considered gauche.

If one could achieve all this by using a feather quill then so much the better.

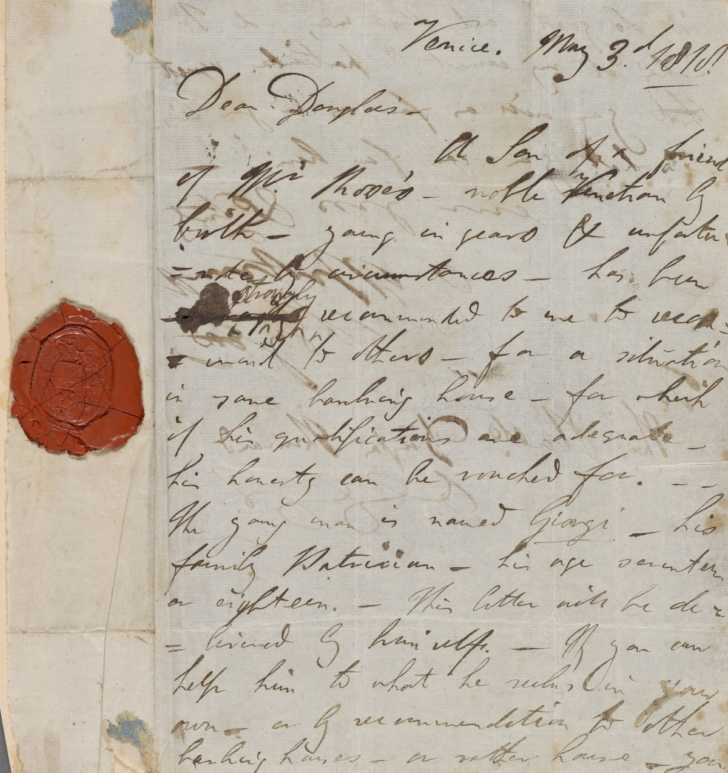

Dates Are Crucial

In Victorian England letters were delivered by the postal service multiple times per day, enabling people to get same day responses for social events, business affairs, and travel plans. With so many letters flying around having each one dated was critical to good record keeping and again implied that you were a person of your word and not trying to be vague.

For people who may write to each other almost daily for years or months at a time dates were important to keep everything straight.

Signed, Sealed, Delivered

It was okay to have one’s monogram printed on the letter paper itself, but was thought of as “egotistical” to have it likewise printed on the envelope. This often applied to women or men of rising social status more than lords and male members of the upper classes. The well-to-do menfolk would have sealed their letters with wax imprinted with their family crest.

The exception to the monogram guideline was that if one was using a wax seal your wax stamp could discretely display your initials. Women were not to use their family coat of arms unless they were bonafide heiresses.

The list of dos and don’ts for writing letters in the Victorian era extends far beyond what we have space for here, but needless to say there was a mind-boggling amount of strictures to follow in order to maintain one’s standing in society. After all, nothing was worse than losing face to your friends and colleagues.

SKM: below-content placeholderWhizzco for DOT