Ice Cream and Cigarettes- The Secret World of Newsies in 1900

They made the best of some bad situations.

When we think of newsboys from the end of the 19th century, we get images of scrappy boys and young men with thick accents and plenty of moxie. The newsies of New York City were part of a whole other world, one where children worked all the hours they could in order to make ends meet, in a city where adults did not inherently care about their welfare. But, these boys also made their own world- one where no small portion of their earnings went towards the unlikely combination of ice cream and cigarettes, where close knit groups stayed in boarding houses together or slept on the street in familiar hidey holes.

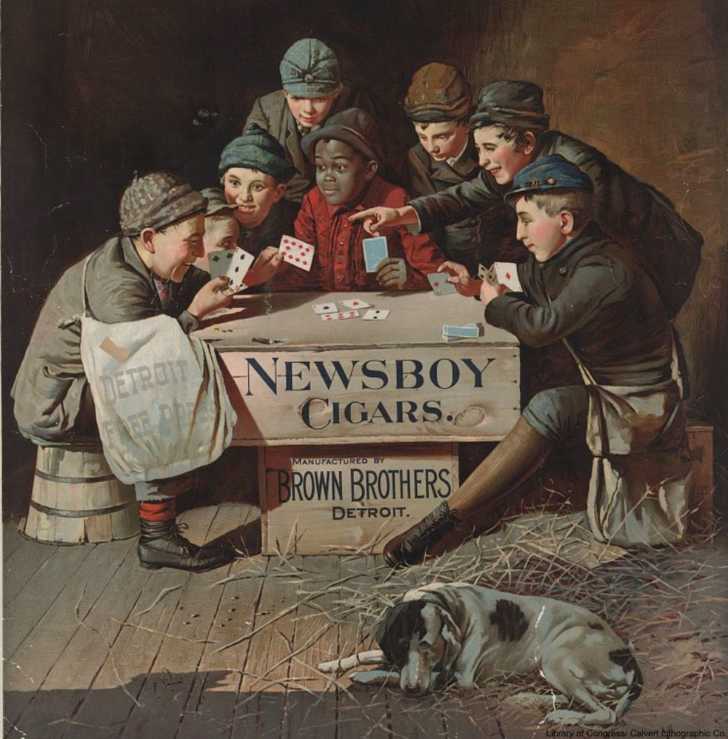

Somewhere between Peter Pan’s Lost Boys and the ne’er do well Little Rascals, these boys were essentially contractors for the newspaper companies. They crafted their own social scene, and could frequently be found gambling on the street, in abandoned buildings, or in their boarding houses. Newsies raised funds from their own pockets for a fellow newsboy’s funeral (an event more likely in those years) and they followed ceremonies of their own making for their dead. At once symbols of youth and yet already so world-wise, newsies occupied a distinct space between adults and children.

Like Curly and Tootles, nearly all of the newsies around the turn of the century were orphans or otherwise had no adults to look after them. Large numbers of minors chose to employ themselves rather than become wards of the state or work in factories. The independence of selling newspapers on the street, however poorly paid work it was, seemed preferable to the alternatives. Not just the work or the lifestyle, the fact that the other newsies were the only family they could rely on made them a closely knit bunch. And, for bargain prices, newspaper companies had at their disposal an energetic army of young people to distribute their products.

The newsies’ great concern for each other and fidelity to their profession was no more apparent than in 1899 when thousands of them banded together to strike against the rising wholesale price of newspapers. The price had been increased from 65 cents to 85 cents during the Spanish-American War and the two biggest papers at the time, William Randolph Hearst’s New York Evening Journal and Joseph Pulitzer’s New York Evening World both fought them on this point, claiming that they would lose too much money if they lowered the price to pre-war numbers.

The system at the time was that the boys would buy a bundle of 100 papers, in turn selling them to the public for a penny a piece. This meant that the maximum amount of money a newsie could make in a day was anywhere from 15 to 35 cents, though many made less than that, and it was a tenth of what a man would make in a day. Selling into the night to try unload every paper was common for many of these underage workers. For the extremely profitable newspaper companies to ask 85 cents was essentially asking the boys to take a pay cut. Not only that, but now any unsold papers would represent even more lost money for the boys.

So they took to the streets. At first it was a small number of kids, but through word of mouth the number grew to reach thousands. The striking newsies stopped traffic, burst down doors, and shouted at the tops of their lungs. Had they not been reliant on each other and all stuck in the same boat, it is quite possible that no one would have taken them seriously. And, while they did not achieve their ultimate goal of decreased paper cost, Hurst and Pulitzer did agree to buy back unsold papers at the end of the night. Still, it would be years before the lifestyle that newsies lived was considered inhumane and systems put into place to keep children from living on the street and working exploitative jobs.

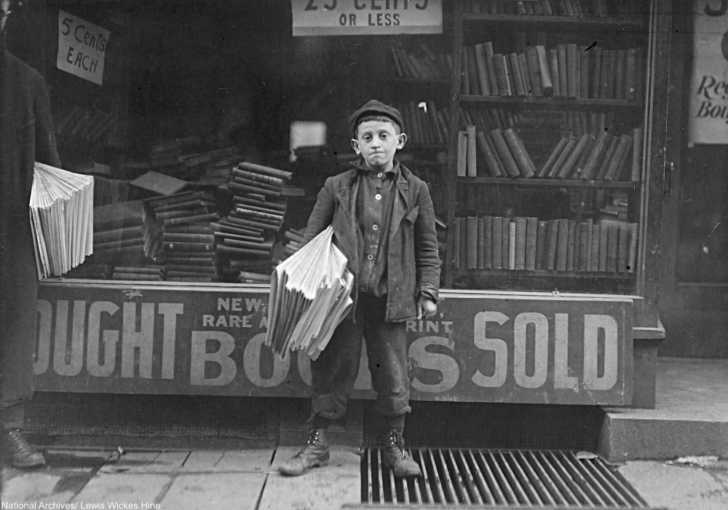

Many of these images come from the work of Lewis Wickes Hine, a photographer and defender of children’s rights. Hine’s work was used as evidence of the harsh treatment of the underaged, immigrant, and female workers of the United States. Mainly working from 1908 onwards, Hine’s photographs show the many ways in which these kids were struggling to get by and the joys they eked out from a meager living. The fact that significant changes to labor laws and employment standards had not changed in the years after the 1899 strike meant that the newsie way of life continued on for decades, despite Hine’s moving photographs and attempts at more progressive labor legislation.

Other strikes occurred in NYC and many other cities for years. Following the 1899 the strike, associations and organizations were formed to help the boys out, like the Newsboy Protective Agency in Cincinnati. But, it wasn’t until 1938 that child-welfare and labor laws regulated how much minors could work. While it persisted, the life of the newsies was a world all its own, with rules and games known only to those who moved within the unique confines of poverty, youth, and stolen moments of freedom.

SKM: below-content placeholderWhizzco for DOT