How Japanese Americans Used Art to Help Them Survive WWII Internment Camps

So much work went into these pieces.

Shortly after the Japanese Imperial Navy Attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the US declared war on Japan and formally entered the Second World War. Soon after Japanese elders, many of them leaders in their communities, were arrested for fear that they might communicate with Japanese forces abroad. By February a system of “relocation camps” had been created under Executive Order 9066, filled with Japanese immigrants and their descendants. The incarcerated had broken no laws and many were American citizens. To add insult to injury nearly everyone in the camps had their property and assets frozen or dissolved as part of the round-ups.

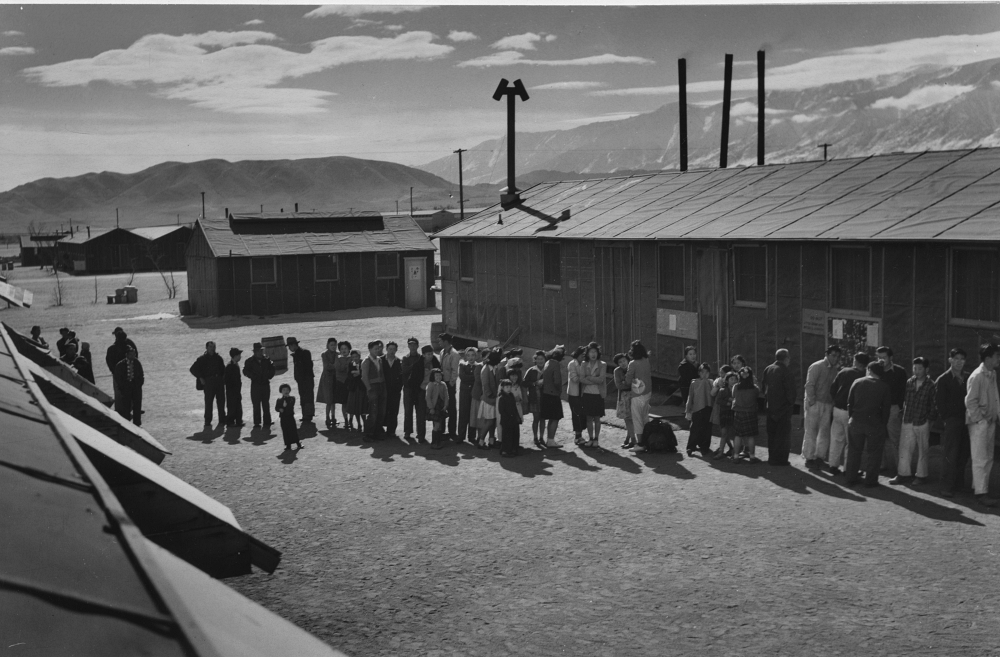

Inside the sparse and hastily-raised camps backless, unfinished wooden benches served for seating in the dining areas. The living quarters were poorly insulated and contained few amenities- even windows were heavily spaced. The areas of country that were swept had higher concentrations of Japan Americans (called Nisei): Washington, California, and Oregon. Relocation camps were set up in Idaho, Arkansas, California, Utah, Colorado, Arizona, and Wyoming.

Department of Justice camps for the older generation of Japan-born residents (or Issei) that were arrested just after Pearl Harbor were also set up in Texas, Idaho, North Dakota, New Mexico, and Montana. All camps were located as remotely as possible to avoid all potential communication to the outside world from the internees.

Once inside the camps life went on, but not without many trials. Dances for the young people were held, schools were cobbled together, and barbershops opened up within the camp gates. To pass the time and keep the prisoners busy art classes were held by fellow inmates.

In the Buddhist tradition gaman is practiced as a way to ensure that the people around you maintain their comfort. Gaman is a means to persevere and the practice of gaman is often associated with keeping one’s problems to themselves. “Keep calm and carry on” was the British version of such a concept during the war, but Japanese gaman can be applied to personal hardships as well as national ones.

It is gaman that was said to be responsible for the rapid response and continued optimism after the 2011 earthquake and ensuing tsunami in Japan. But, in the internment camps this way of surviving often went hand-in-hand with making art.

While some artists were imprisoned, many of the people making art in the camps did not consider themselves artists. Instead, they passed the time using a mixture of art therapy and gaman. While the materials offered to the camp inmates were by no means extravagant, there were some art supplies and carving tools available.

Those wishing to make more elaborate works had to get creative with their materials. It wasn’t unusual for inmates to assemble rocks or shells in order to make their unique artworks stand out. Scraps of fabric were made into quilts and coats, Disney characters were made from shells, and playing cards were made from scrap electrical paper board. In place of real flowers, bouquets, and corsages used for weddings, funerals, and other events, internees made paper bouquets and corsage pins of shells arranged and painted to look like flowers.

The items made were numerous, from furniture to watercolor paintings to jewelry and wall hangings. However, most of the art that was made in the camps was destroyed decades ago.

Author and editor, Delphine Hirasuna, became fascinated with the subject when she acquired a small, wooden bird brooch that was made in one of the camps and passed down through her family. She received so many compliments on it that she decided to research what was at the time a little-known topic. What she found was that when the inmates were released in 1945 most people simply threw out the art they had made in the camps. In her first book on the subject, The Art of Gaman: Arts and Crafts from the Japanese American Internment Camps 1942-1946, she sought to photograph some of the few pieces of camp art that were left.

In an interview Hirasuna estimated that for every piece of camp artwork that survives today, somewhere between 10 and 20 were thrown out. At the time the artwork items were each seen as yet one more detail to take care of at a time of great stress. The return to society was bleak for most internees – marred by the loss of land and property, discrimination, and even posses that shot the windows out of the homes of returning families.

Many of the smaller items were never signed which makes identifying camp artwork difficult when there isn’t a family provenance to rely on. Hirasuna documented yet more works in her second book on the subject, All That Remains: the Legacy of the WWII Japanese American Internment Camps. However, exactly how much internment camp art has been lost will never be known.

SKM: below-content placeholderWhizzco for DOT