The Former Enslaved Man Who Went on to Write an Autobiography

His survived a harrowing time before and after the Civil War.

Born into slavery in Winchester, Kentucky, in 1845, Peter Bruner had escaped the tannery where he was held during the Civil War, only to be told that it was a “White man’s war” when he first tried to join the Union Army. Bruner, however, tried several more times to join up -until he was finally accepted at Camp Nelson, renowned as a place of refuge for escaped slaves. He went on to live a productive life and even wrote an autobiography, the latter being very much a rarity.

By some accounts, Bruner was illiterate and it was actually his daughter, Carrie, who transcribed his autobiography and she is listed as his editor. However, an account of his life from 1936 states that he did -for a short time- attend school as an adult.

His book, A Slave’s Adventures Toward Freedom Not Fiction; But the True Story of a Struggle, was first published in 1918. The volume contains a detailed account of his life, as well as some tongue in cheek humor, such as descriptions of “what nice work” the job of hauling water by hand is.

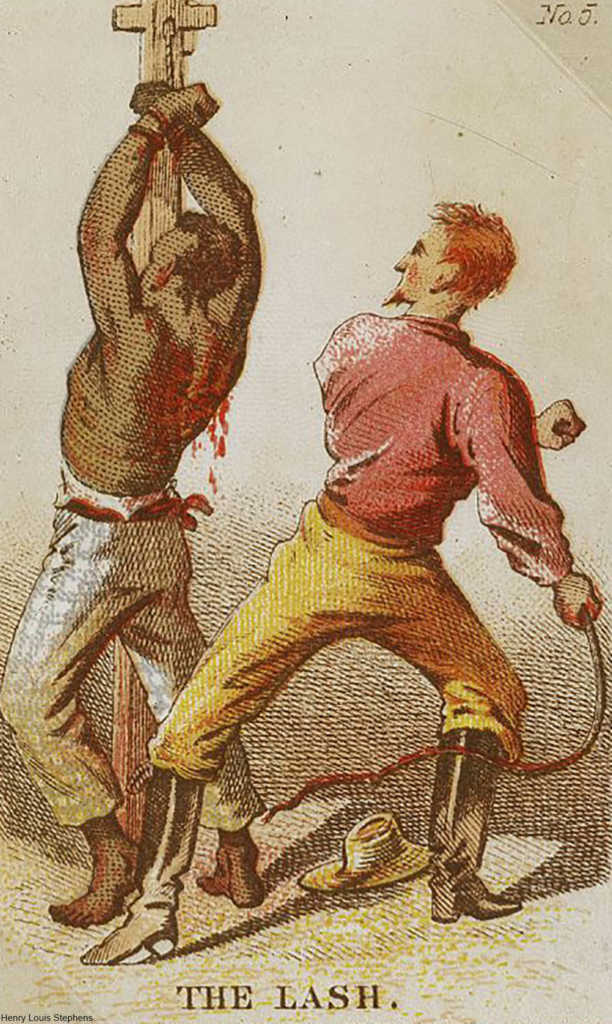

While enslaved, his masters had been the brothers John and Joe Bruner, who owned tannery operations, the latter of whom the former servant thought had been a good man. Of his former master he wrote, “He never would whip me very much not more than two or three times, sometimes he would kick me every now and then, but I did not mind that for I was used to such hardships those days.” Peter’s mother had been a slave and his father was reportedly John Bruner, who took to whipping him for small troubles and denying him food and blankets when the child was only about 10-years-old. This was when he heard his masters talking about how it was time to “break us in” (referring to the children) as Bruner recalled it.

His master’s drinking only led to more whippings, some carried out using a special leather strap made just for slave beatings which was dipped in saltwater so that welts and scars would be inevitable.

Such extreme cruelty led Bruner to escape many times, but each time he was brought back. And, his treatment worsened after each time he escaped until finally special shackles were placed on him that so that he could not run away during the night. After the Union Home Guard forced John Bruner to remove the shackles in 1863 and imprisoned him for a short period, Bruner ran away one final time.

After 1864, it became law that escaped slaves who served in the Army were automatically emancipated. Bruner served in the in the 12th U. S. Colored Heavy Artillery Regiment –Company G. He worked for a short time in medical, but found it so grim and nauseating that he requested to be on front lines again. There he suffered frostbite and had an episode of Variloid- a mild remission of smallpox in someone who has perviously caught the disease or been vaccinated.

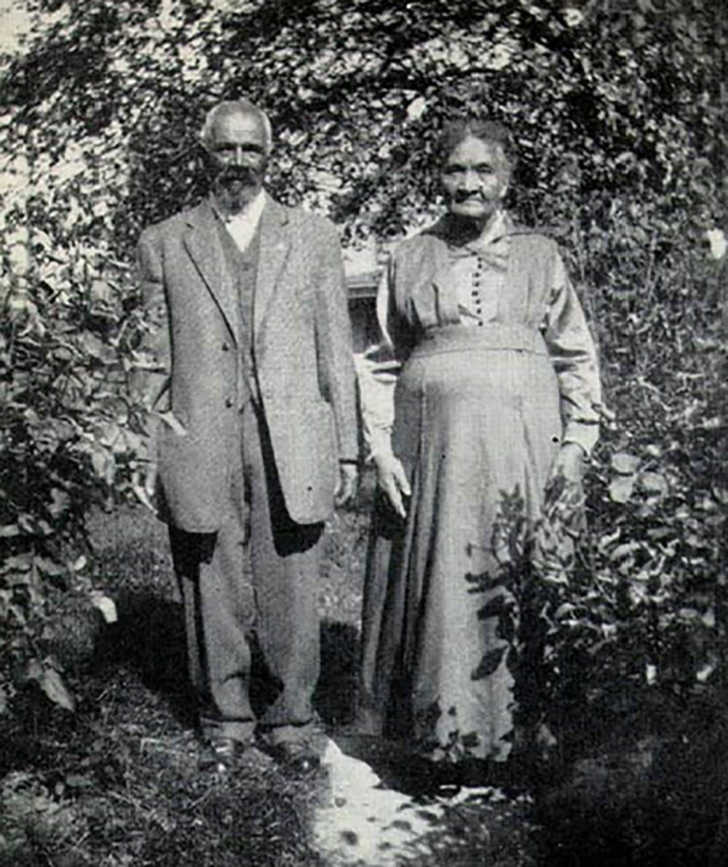

Bruner served in the army until 1866 at which point he moved to Oxford, Ohio, where his aunt and uncle lived. He married Frances Procton in 1868 and they went on to have 5 children.

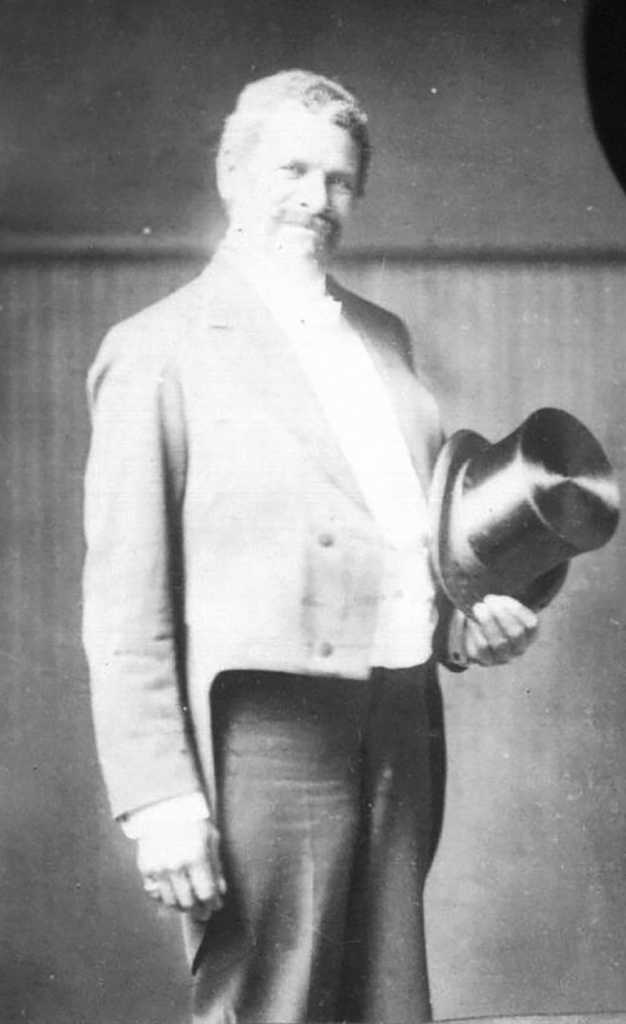

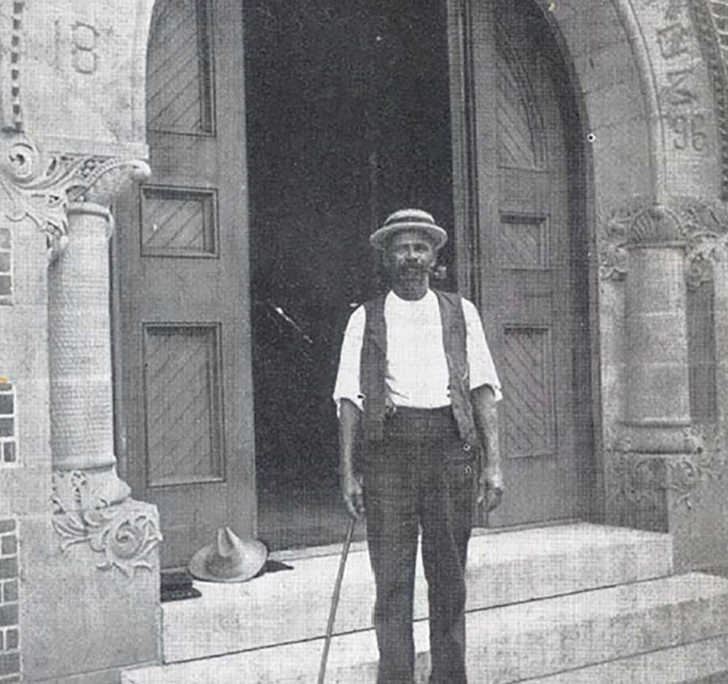

Bruner went to work at as a night watchman (and later as a construction worker) at Oxford College, where he was widely respected and was thrown a 25th wedding anniversary party by the staff. Later in life he was offered a janitorial job at Miami University in Oxford, where he worked for a number years and where staff threw him and his wife their 50th anniversary party.

In addition to writing abut his life as an enslaved person and his troubles in the period following the Civil War, Bruner was interviewed by the Works Progress Administration as part of the Slave Narrative Project in 1936. This was only two years before he passed away.

Due to his efforts and hard work, his children and grandchildren were able to attend college, something which was out of reach for many Black families during the Reconstruction era. In fact, Bruner was nearly led to financial ruin owing to potential deals that had gone awry at the last minute. It was not uncommon for White businessmen to simply breech contracts with Black people during this era, as now-free former enslaved people were seen as direct competition for jobs and in business dealings.

Some have argued that Bruner was seen as more of a mascot by his academic employers, without ever being regarded as an equal to his White colleagues. However, Bruner requested that (upon his death) his famed top hat be returned to Miami University where it remains to this day.

SKM: below-content placeholderWhizzco for DOT