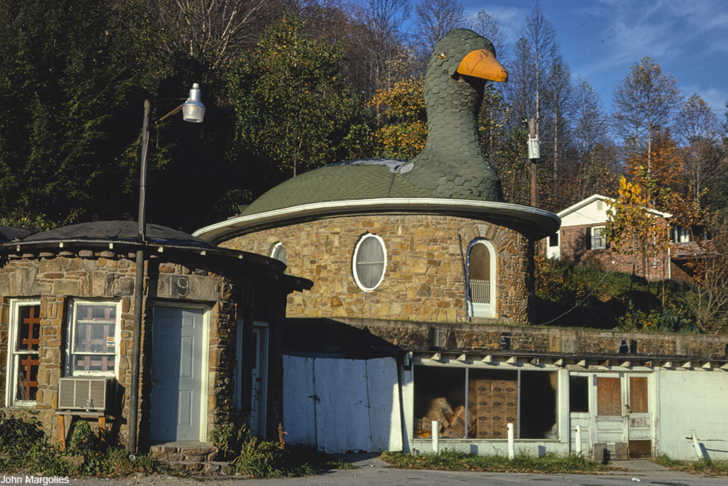

America’s Lost Fascination with Duck Architecture

Buildings like these are pretty rare these days.

In the 1930s people would have done nearly anything for a buck. This included devising all kinds of ways for others to willingly part ways with their cash. At the same time that the Great Depression struck many with financial woes, the rise of the automobile made roadside attractions and highway tourism a common way to make money. Restaurants and general stores competed for travelers’ attention through flashy architecture that usually announced from miles away what they were selling -or at least made people want to take a closer look.

The outsized novelty buildings not only were a visual beacon, they were also considered a attractions in their own rights. If you weren’t really hungry, you might still stop and have a cup of coffee at a diner shaped like a giant milk pail, just to say you had.

This type of architecture was often merely decorative, though some establishments were functional from top to bottom – even the parts built for novelty. Some towns or businesses even took to making their water towers into novelty shapes so as to draw attention to their main streets. With lots of migration due to the Dust Bowl and people looking for work, a lot of people were on the road and passing through these small towns with a frequency unknown before the Stock Market Crash of 1929.

These types of novelty structures became known as “duck architecture”. The name comes from a Long Island poultry farmer who built a giant building shaped like a duck in 1931 in order to sell his products, though novelty buildings predate the 20th century.

Today, most of these novelty buildings are long gone, as America’s fascination with roadside attractions is now as faint as the family car trip to the Grand Canyon. Most people nowadays fly wherever they visit, leaving little car traffic to make the upkeep of these buildings worth the cost. Many examples of kitschy duck architecture have also been labeled as “tourist traps” which has not helped them survive.

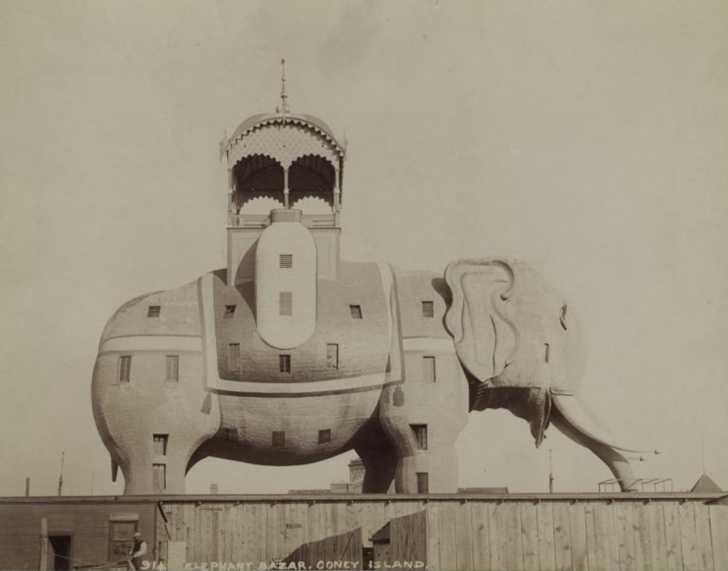

There are couple of notable exceptions to the dwindling of duck architecture, such as Lucy the elephant at Coney Island. She was built in 1881 as part of the seaside attractions there, and for a few years was in bad repair. But, she was recently refurbished and kitted out for Airbnb guests- and then sold through bookings in a matter of minutes.

A recently-built example of duck architecture is the Longaberger basket building in Newark, Ohio. The company was founded in 1973 and in less than 20 years became the premiere name in handmade baskets. In 1997 the building, known as the Big Basket by many, was built to house the company’s headquarters. They moved their operations to their manufacturing hub in Frazeyburg, Ohio in 2016 and left their headquarters to be sold. Like Lucy the elephant, the Big Basket was recently bought and was turned into a hotel.

Americans may have lost the desire to visit roadside attractions, but it would seem that staying overnight in a novelty building holds some exciting promise for many travelers.

SKM: below-content placeholderWhizzco for DOT