The Often-Sad History of the Dollar Princesses

Money couldn’t protect them from heartbreak.

They were rich, beautiful, had experience with the finer things in life, and were willing to leave their families in America behind in exchange for castles, titles, and the chance to mother the future leaders of the world. This is how many of the so-called “dollar princesses” of the late 19th and early 20th century have been characterized. But, the truth behind their glamorous lives was often a lot less illustrious than what we’ve been led to believe.

One of the first American women to become titled in England was Lady Randolph Churchill (also known as Jennie Jerome Churchill), mother to Winston Churchill. She was born to a prominent mother and financier father, but was educated in Europe following an escape from her father’s personal scandal back in the U.S. She later met Lord Randolph Churchill, third son of the Duke of Marlborough, and the two were married in 1874.

Though this marriage appeared to be one of love and passion, the parents of both the bride and the groom argued at some length over the financial particulars of the union, delaying the wedding by many months. Much of the bride’s fortunes were later spent on gambling debts incurred by her noble husband.

Upon marrying Jennie became Lady Randolph Churchill and this set the precedent for other American women that they, too, could receive a title if only they married in. But, other pairings -often made from the aristocrat’s clear position of needing money- were sometimes completely devoid of any joy at all.

For years the upper crust of England had relied on the earnings of their estate farms, land holdings, and investments to support their lavish lifestyles. They lived in castles and manors built during times when they seemed too prosperous to ever need to worry about the cost of maintaining such grand homes. And, while many of these titled families were land and home rich, they were increasingly cash poor. At the time it was seen as bad taste to hold a job as an aristocrat, yet the unemployed heirs of England often spent more money than their estates alone could recoup.

All this meant that when it came time to find wives for their sons, many were pushed by their families to take on American debutantes solely for the hefty dowries that came with them. These debutantes were also pushed into marrying English aristocrats so that their wealthy families could gain social status by saying they had a duchess in the family.

One of the worst cases of these mismatched pairings was that of Consuelo Vanderbilt, who married Charles Spencer-Churchill, 9th Duke of Marlborough, in 1895- one of the first celebrity weddings. Thrown into the position of inheriting a title and massive estate with no money, the duke sought the quickest and presumably easiest solution: marry an heiress.

Consuelo’s father, William Kissam Vanderbilt, had made his fortune through railroads. Her social-climbing mother turned her daughter’s potential suitors into a way to further boost the family name. The match was made by an American dollar princess herself, Lady Mary Paget, and Consuelo was forced into marrying a man she did not love.

Indeed, both parties were reportedly already in love with other people -a fact that neither got over. She later wrote of her wedding day that instead of happiness she felt incredibly sadat having to go through with something she so vehemently opposed. The pair was divorced and the marriage was later annulled, but not until after the Vanderbilt millions saved Blenheim Palace.

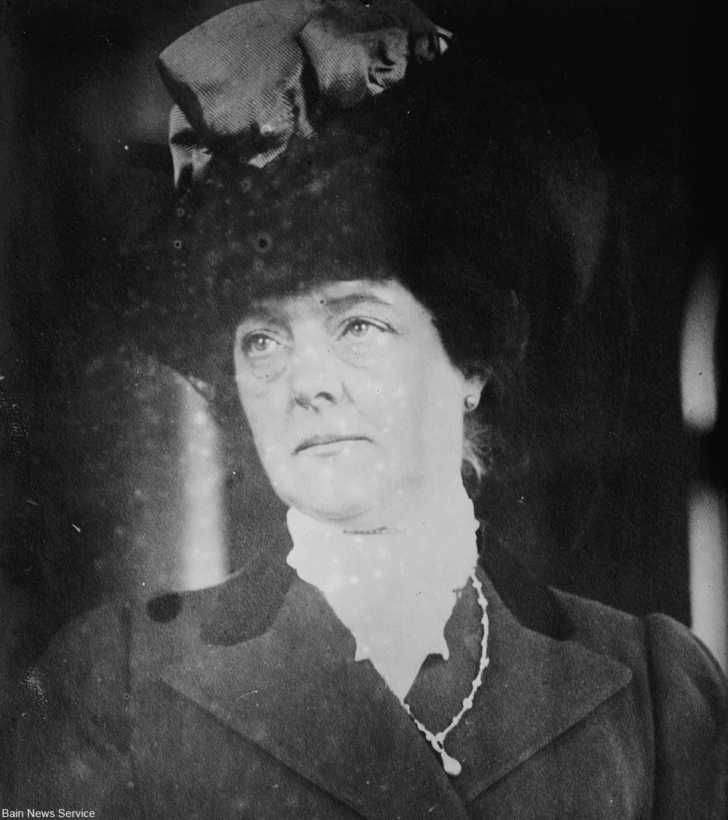

Another million dollar princess was Frances Ellen Work, later known as Mrs. Burke Roche and later still as the great-grandmother of Princess Diana. Her father, Franklin H. Work, had made his fortunes in stocks and was mentored by Cornelius Vanderbilt. After 3 children and 11 years of marriage, she divorced her husband, a man who later inherited the title of the 3rd Baron of Fermoy, charging him with desertion. Her father was opposed to the unhappy marriage and even called for international marriages to stop altogether, after disinheriting her.

Frances’ dowry of $2.5M was used to fund an extravagant lifestyle and a host of gambling debts of the then-future baron. Frances, in an ironic twist of fate, was divorced from Burke Roche before he became baron, meaning that she herself never received a title.

It’s easy to say, a century or more after the fact, that these women were only looking to gain a title, but the truth is that the nobility were on the prowl for the injections of cash that American heiresses brought to the table- and love often played no part.

SKM: below-content placeholderWhizzco for DOT