Skeletal Evidence Suggest Medieval Woman May Have Been a Rare Female Scribe

The clues came from the plaque on her teeth!

Blue pigment in the Middle Ages was a very costly substance, made through very labor intensive methods and from exotic ingredients. Ultramarine blue was the best blue at the time and was derived from the semi-precious stone lapis lazuli, which was then ground into a powder and made into a paste.

At the time the only known deposits of lapis lazuli were in Afghanistan, which meant that Europeans had to import it at great expense. Only the best medieval scholars and artists would have had access to these materials, which makes the discovery of this pigment on a nun from the era all the more astounding.

The blue was used, along with other costly materials, to color the pages of illuminated manuscripts. As such only the most skilled of artisans were allowed access to these luxury art supplies lest some of the pigment go to waste.

Most often the work of Catholic monks, these manuscripts were holy texts: the only reason for literacy for many at the time. Each page was meticulously copied and adorned by hand, and the tip of the brushes were usually licked to a point by the artisans to get the cleanest lines.

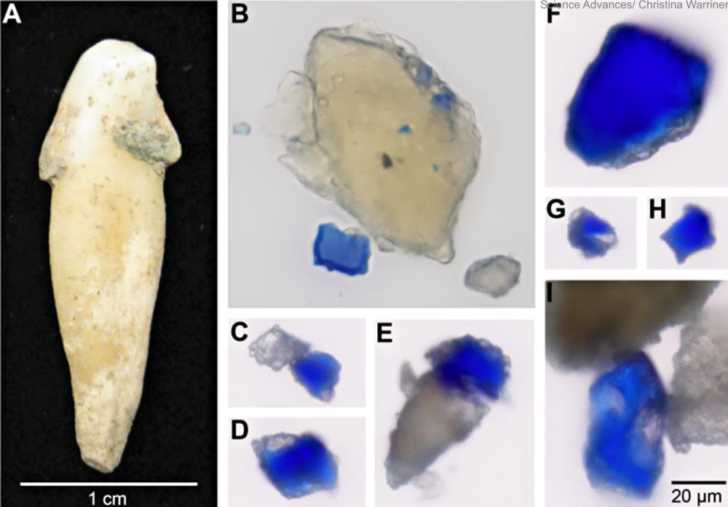

When blue pigment was recently found in tooth plaque of a skull from a medieval woman, known only as B78 to archaeologists, scientists came to believe that she may have been a scribe as well- something that is rarely discussed in history books.

The skull was found in an unmarked cemetery for religious members near the more modern church of St. Peter near Lichtenau, Germany, and radiocarbon dating puts her lifespan sometime between the 10th and 12th centuries.

The multidisciplinary team of scientists was on this study was led by Christina Warriner, an archaeologist who focuses of on dental findings.

The religious community she belonged to was destroyed by fire in the 14th century, so there aren’t clear records. But, the woman was estimated to have been between 45-60 when she died, with no signs of trauma or infection- an incredible life spanfor the era. The remains of B78 were also free from occupational stress, a sign that she may have been of high birth. The teeth of the skulls found at the former Dalheim monastery were initially examined to discover the oral microbiome of the subjects.

Pigment in the woman’s teeth was tested against smalt, a pigment made from the crushed cobalt glass, but was found to be nearly identical to reference lapis lazuli samples. Furthermore, smalt wasn’t in common use in Europe until the 16th century or later, which makes the lapis lazuli fragments in the teeth all the more amazing. During this period ultramarine pigment from lapis lazuli would have been more costly than gold!

The archaeological team also suggested a few other possibilities as to why this woman would have blue pigment in her teeth, such as: the preparation of artistic materials for others, devotional kissing of sacred illuminated texts, or the use of lapidary medicine. But, the most likely scenario is that she was in fact a scribe.

If this was her role then it leads to many more questions. Was some of the work that was previously thought to be made by monks actually made by nuns? How widespread was literacy among women medieval times? Which manuscripts might she have worked on? Many of these questions at the moment have no answers since illuminated manuscripts were left unsigned as a matter of course until about the 15th century. But, the idea that women were more involved in manuscript making than previously thought does shed more light on the history of Christianity.

SKM: below-content placeholderWhizzco for DOT