Benjamin Latrobe and HIs Most Beautiful House

Benjamin Latrobe and HIs Most Beautiful House

Sometimes a person who lived long ago captures our imagination. This is Nancy with Dusty Old Thing and, for me, it’s Benjamin Latrobe. Maybe it’s because he was handsome. Maybe because of his design ideals and genius. Maybe it’s because he was mercurial. Maybe it’s because he had debt and loss and hardship. Maybe it’s because he designed a house in Kentucky that captures all those things.

Latrobe was born of Moravian parents in England in 1764, educated in Europe, then learned engineering and architecture. He had a hard time collecting payment for his work in England, his wife died in childbirth, and he suffered a breakdown. Inspired by the ideals of the new Republic, he immigrated to the United States in 1795. He was the second Architect of the Capitol, appointed to rebuild it after the War of 1812. He designed the Cathedral in Baltimore, parts of the White House, St. John’s Church, and many other public buildings, churches and private homes mainly in Pennsylvania, New York, Virginia, Maryland, Washington DC and Kentucky. He designed and supervised the building of public works: canals, a prison, water works, turnpikes, bridges, the gate to the Navy Yard.

Latrobe must have driven himself hard. He was prolific but critical of others, including L’Enfant. He wanted his projects to match the ideals of the Republic. He made and lost powerful friends and positions over questions of design, construction, payment and political alliances. Finally, believing that trade down the Mississippi would bring growth and prosperity, he left the East Coast for New Orleans, hoping to recover financially. He built the State Bank of Louisiana and began work on a new water supply system for the city, a project meant to lessen the threat of yellow fever. It ended up taking first the life of his son Henry and, then, his own. He died of yellow fever in 1820. His remains were picked up from his hotel by the “dead wagon” and interred in Saint Louis Cemetery in what was probably a common lye pit. The exact location is unknown; a plaque was erected by his descendants in 1904 at a spot considered likely.

Today Latrobe’s portrait hangs in the White House Map Room. PBS produced a special on him in 2010. A 769 page book, The Domestic Architecture of Benjamin Henry Latrobe by Michael Fazio and Patrick Snadon, is full of his drawings and details of his work.

But the most beautiful house?

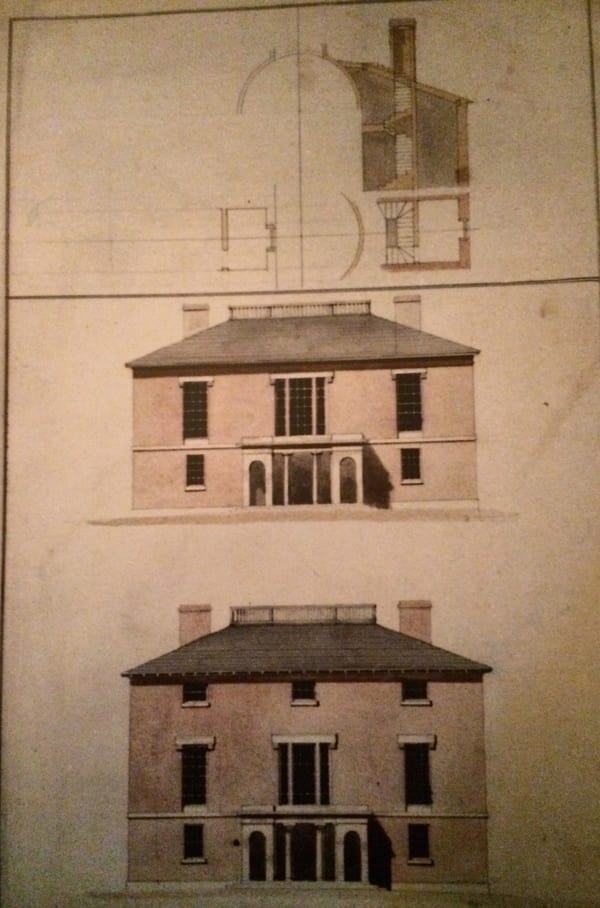

For me, it’s Pope Villa in Lexington, Kentucky, now resurrected by The Blue Grass Trust for Historic Preservation. It was built in 1810-11, in a new style. It was then, and still is, avant garde. Latrobe designed it for John and Eliza Pope. John was a US Senator from Kentucky. Eliza was the sophisticated sister of John Quincy Adam’s wife Louisa.

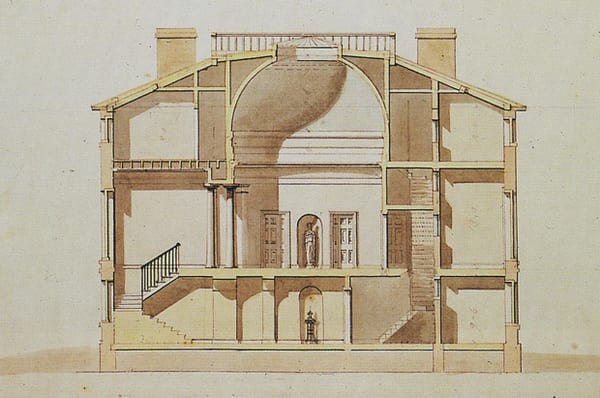

Latrobe liked for rooms to flow without a central hall. He didn’t like service ells, preferring that all rooms should be in the central block the house so that the vistas from all sides could be appealing. His exteriors were austere. He liked to create, inside, a progressive set of scenic rooms that evoked the idea of small temples. He liked rotundas within structures. He liked the use of the oculus for light. You can see those ideals in his design for the Pope’s Lexington house.

The Popes, too, had reversals. They only lived in the house for a few years before renting it out. Over the years the house had new owners who made additions: ells, columns, balconies and Italianate elements. It was turned into apartments. The University of Kentucky expanded nearby. In 1987, a fire nearly destroyed it. Local preservationists were alarmed and kept it from demolition. The local newspaper featured stories about the house and about Latrobe. The Blue Grass Trust assumed ownership. Over the years, under their guidance, it’s been stabilized, a new roof added, and the facades restored. Today it serves as a laboratory for craftspeople learning old-world skills, part relic and part an avant garde way itself in approaching preservation.

For many of us, we can’t look at a building, or an antique, without giving some thought to its creators and the people who inspired or used it over the years. It’s their stories that are inspiring…in many ways.

SKM: below-content placeholderWhizzco for DOT