The Coney Island Sideshow Origins of the NICU Incubator

Attractions like this were quite common at the time.

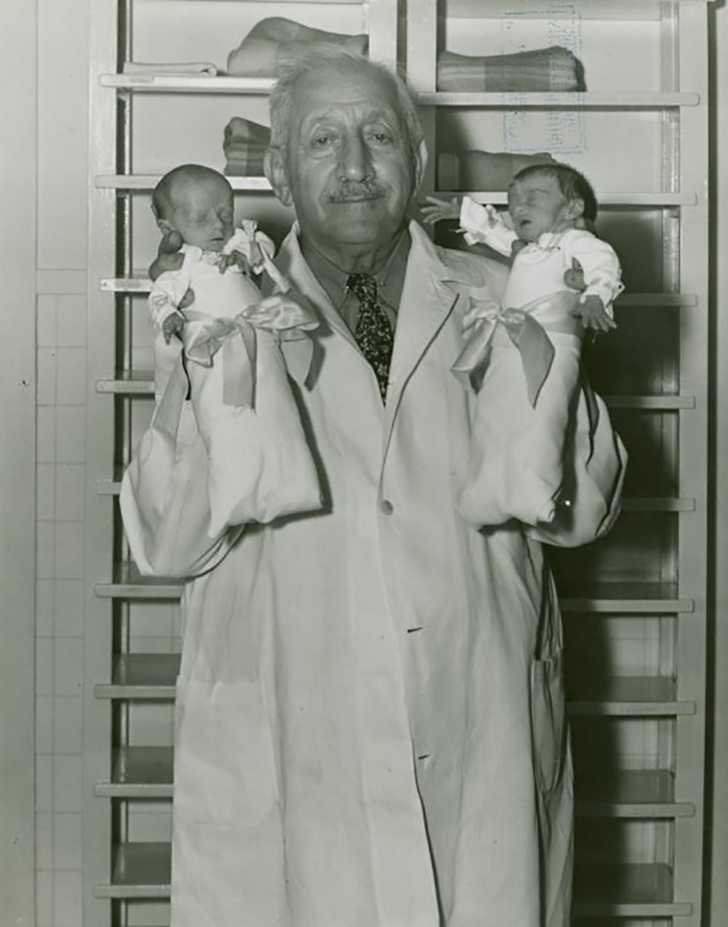

To many people who saw his white coat and staff of nurses, the assumption was that Martin A. Couney was a doctor. His public exhibitions of prematurely-born babies had been successful year after year. Beginning at the end of the Victorian era, Couney had displayed the fragile infants at various World’s Fairs and even at Coney Island.

Couney, however, was not a doctor and ultimately his displays were sideshows that also happened to save live lives. Because of his very public attention towards preemies, it is estimated that as many 7,000 children were allowed to live. And, this doesn’t even include the number helped long after he passed away in 1950.

Couney was a German-Jewish immigrant whose family had a long tradition of becoming doctors, but he was no doctor. He had claimed to have had some medical training, but even that is not well-regarded today. Despite his lack of formal training, Coney had a passion for saving children.

His first forays into the world of infant incubators came when he worked with Dr. Pierre-Constant Budin, a French doctor concerned with infant mortality rates. Budin was one of many French doctors trying to tackle the problem of low birth rates in France and doctors there turned their attentions to the grim infant survival rates of preemies.

Couney claimed to have been an apprentice of Budin’s, but in reality may have actually been a technician for the incubators. In either case, it was under Budin’s command that Couney created the first ever display of children in incubators at the Great Industrial Exposition of Berlin in 1896.

The exhibit was known as the Kinderbrutanstaltor “child hatchery”. It may sound gruesome and like something from a science fiction film to us today, but in the Victorian era (and beyond) many sickly children were not allowed to stay in hospitals.

The widespread (though not universal) belief at the time was that “weak” children should not be given a chance and should be allowed to perish to make way for healthy babies. This theory also tied in with the eugenics movement which had been gaining traction at the time.

While the sideshow nature of the incubator attractions cannot be questioned, the alternative for these particular children was a distinct lack of adequate care – and almost certainly death.

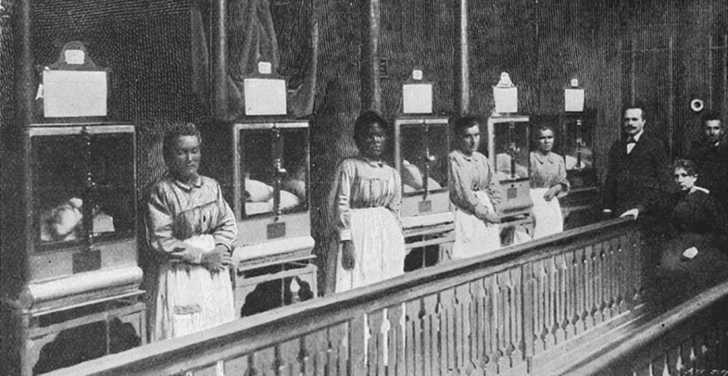

The Kinderbrutanstalt was filled with metal and glass incubators that allowed the crowds to see in. Tiny babies were placed in the boxes, which impressed the fair’s promoters. Couney was asked to come to London the following year for Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee celebration. It was after the popularity of the London show that incubator displays actually became a craze. Despite the outcry from some over the morality of it, incubator shows were quite popular with crowds.

Soon exhibitions of premature babies were popping up all over the place, many of which were operated by Couney himself. Couney employed several nurses and wet nurses to care for the infants, in essence creating his own makeshift Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. In his shows the incubator babies were given round the clock care and the wet nurses had strict rules so that the preemies could have the best chance in life. Many of the babies were too small and too weak to suckle, which made the staff crucial to their care.

It would be many decades before NICUs would become a standard part of larger hospitals, but at the turn of the 20th century, the concept was quite the novelty. Crowds were anxious to see modern science in action, even at the expense of the babies’ privacy.

Over the next few decades, Couney would travel far and wide with his contraptions, giving second chances to babies who weighed as little as 1-3 pounds. While some remained skeptical, Couney had a success rate of 85%, which was unheard of in a era when many preemies died shortly after birth and even babies that seemed healthy didn’t always make live past childhood.

The success stories of Couney’s babies eventually brought medical professionals around the idea and made sure that the concept of preemie care was brought into public view.

Couney did not charge the parents of the preemies he looked after and he returned the children once they had gained some weight. He closed his Coney Island operation, which for years had been a regular gig, in 1943. By that time the first preemie infant station at Cornell Hospital was opening, a sign of the success of Couney’s very public work.

SKM: below-content placeholderWhizzco for DOT