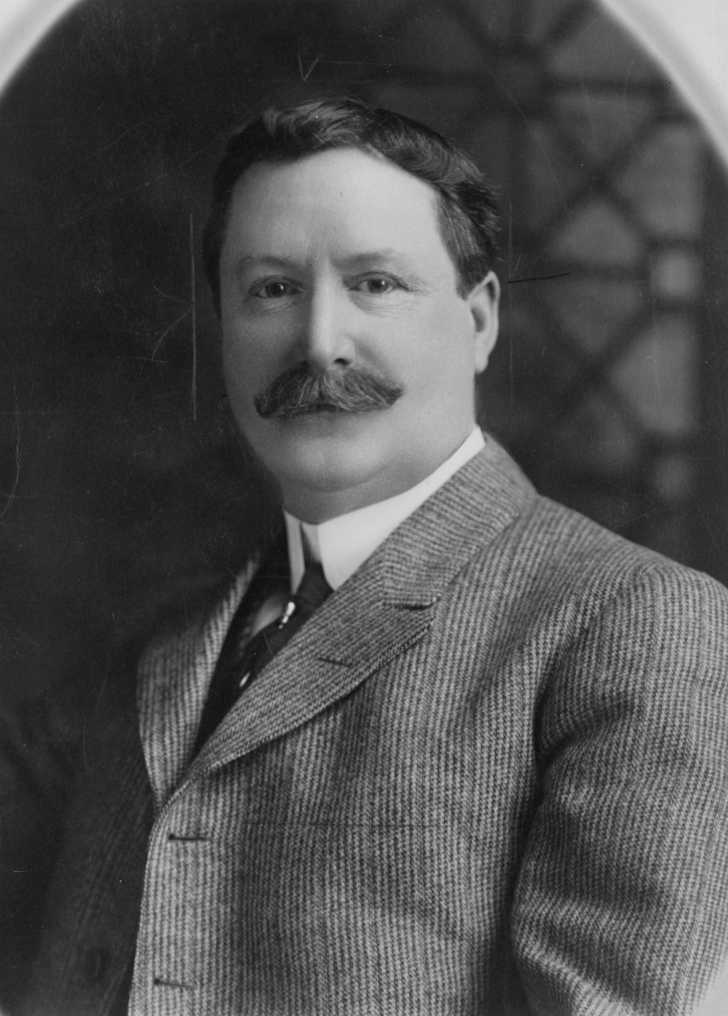

Long before the F.B.I. was formed, private detectives paved the way for later -more official- investigations. In the days before centralized records crimes of land grabbing and fraud were rampant. Some of these fraudsters and counterfeiters were operating undetected for years. Gumshoe, William J. Burns, worked on several high profile cases involving land grabbing and counterfeiting through his detective agency, William J. Burns National Detective Agency. He would later rise to national prevalence and become the top investigator in the U.S. He became known as the American Sherlock Holmes, but today many people have never even heard of him.

Burns was born in 1861 and by the turn of the century he was married with 6 children. His loving wife, Annie, sometimes worked with him on cases, both having been on the payroll of the case involving William Brockway and his near-perfect fraudulent U.S. bonds in 1895. As part of the Secret Service, then an organization that mainly worked to catch counterfeiters, Burns had made a name for himself and then struck out on his own, creating the William J. Burns Detective Agency.

Burns was at the center of the 1910 bombing of the L.A. Times building in which angry iron worker union members bombed the paper in retaliation for anti-union writings. He had been hired based on his previous work trying to catch unionists working for the National Erector Association. His employees at the agency were instructed at times to bribe witnesses or even commit burglary in order to obtain evidence.

In 1921 Burns was hired to become the head of the Bureau of Investigation (B.O.I.), the predecessor of the F.B.I. He would work for the BOI during the most famous scandal of his day, Teapot Dome Scandal, in which former POTUS, Warren G. Harding (then deceased) and other upper crust American businessmen were implicated on charges of bribery, for which only one man ever served time. Ironically, he was personally linked to the case because he had instructed his employees to act in a retaliatory manner towards newspapers that were covering the scandal in an unflattering light.

This led to another scandal and in 1924 Attorney General Harlan Fiske Stone asked Burns to resign from the B.O.I., which he did. Burns was replaced by J. Edgar Hoover, who become the longest-serving director of the F.B.I. (48 years he was in his position) and known skeptic of everyone one around him.

In 1927 Burns was sentenced to 15 days jail time for sending B.O.I. agents to shadow members of the jury in the Teapot Dome Scandal. However, this verdict was overturned by the Supreme Court.

During this period, not only was Burns well known for his sleuthing, but he was also a prolific writer of crime mysteries. He wrote dozens of short stories, some based on true cases, involving crime and mystery. Many of these stories were made into film shorts to satisfy the public’s hunger for stories brought to life on the big screen. It makes sense that he would choose this subject to write about since clearly he was fascinated and (and at times) absorbed by his work.

Burns’ transitions from celebrity P.I. to director of the B.O.I. to writer/actor makes him not only the American answer to Sherlock Holmes, but also a Sir Arthur Conan Doyle type figure, someone who not only solved crimes but also brought the genre of true crime into popularity.

Burns died suddenly of a heart attack in 1932 in semi-retirement in Florida, though he had been making appearances in film as recently as only one year before his death. In 1930 and 1931 Burns appeared in 19 films, proving that he had a real flair for both crime stories and storytelling.

SKM: below-content placeholderWhizzco for DOT