Turn of the Century Street Harassers Were Called “Mashers” & Women Fought Back Hard

They didn’t have #MeToo, but they challenged harassers in their own widespread movement.

In the news and on social media we hear about sexual harassment and catcalling on what seems like a daily basis. The #MeToo movement has gained publicity as more and more women share their stories of sexual violence. While anyone can tell you that street harassment is not a new phenomenon, many people don’t know that back in the 19th century men harassing women on the street were known as “mashers” and ladies formed their own movement to end unwanted attention on the street.

The Origin of the Masher

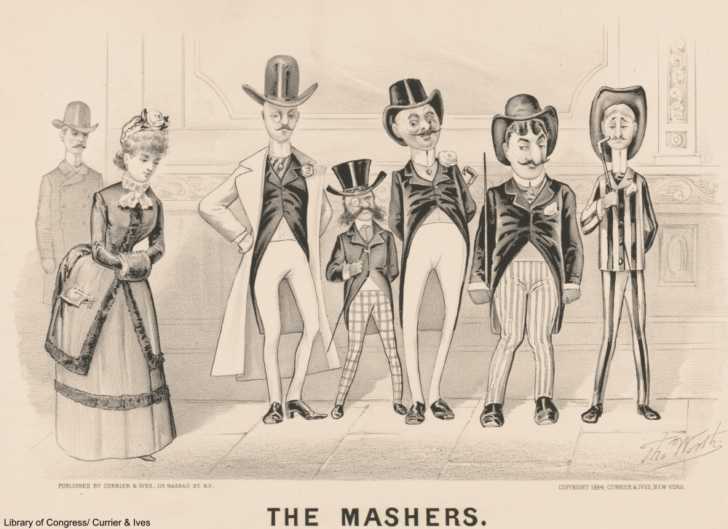

The term “masher” initially referred to an outlandish dandy, the word derived from a humorous conversation between 2 comedians. At the time, it was considered proper for potential suitors to be introduced to ladies in formal settings. For a woman to be approached on the street in the first place was considered quite boorish and mashers eventually became associated with acting inappropriately towards women in public, in addition to their unconventional fashion tastes.

While society at large was not yet willing to grant women the right to vote, many people believed that women should be able to walk down the street free from unwanted touching or catcalling.

Mashers in the Media

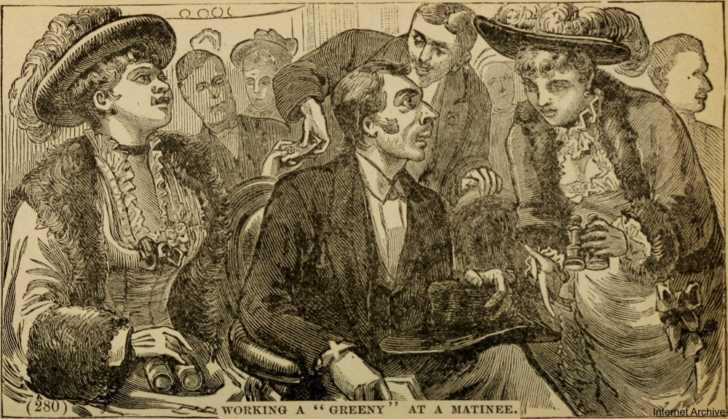

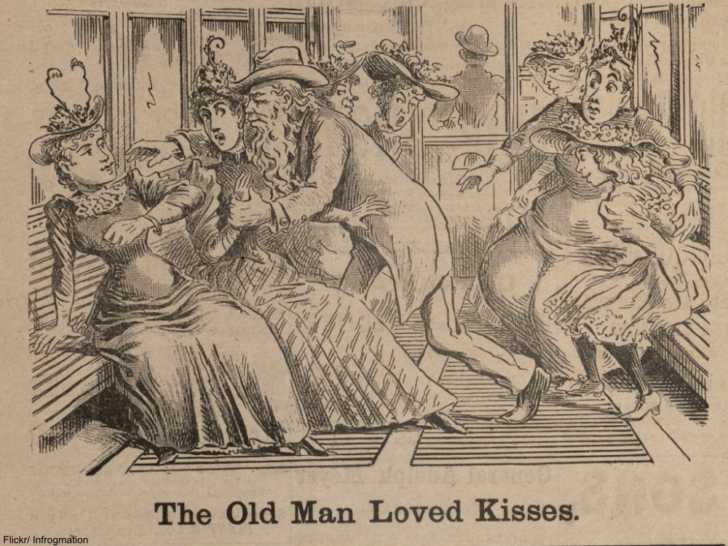

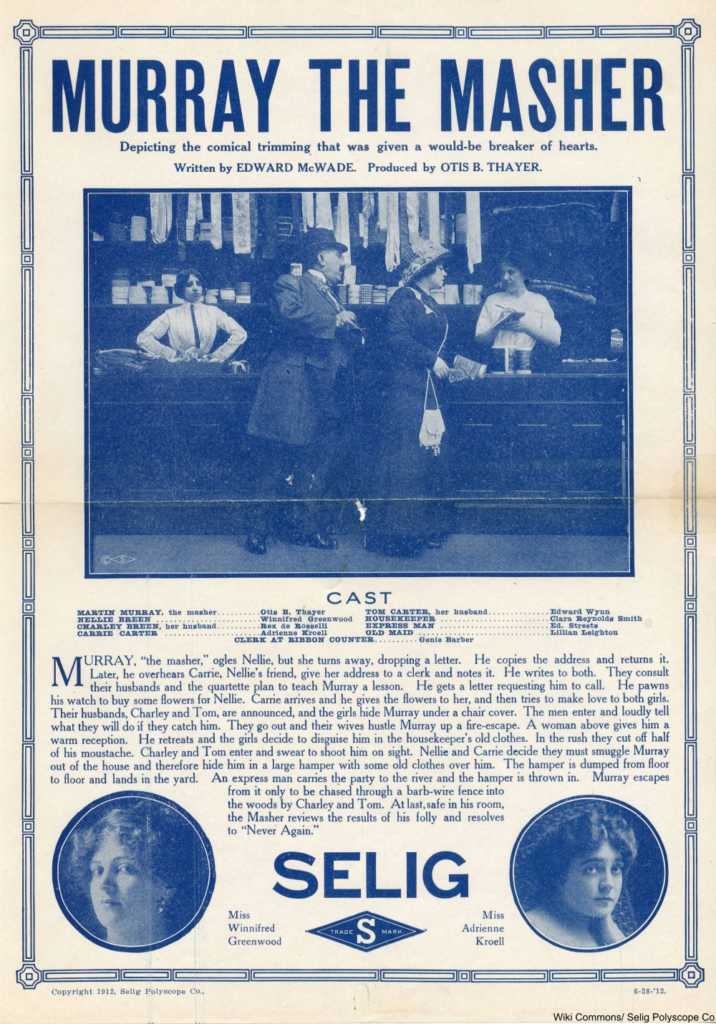

Political cartoons of the era called out masher behaviors as extreme and unwanted, though some of them were drawn from the perspective of the men involved. Mashers were frequently depicted in the media as goofy, demonic, or completely out of touch. Inappropriate street advances were often the subject of complaints by shop girls and women who were going about their daily business unescorted.

One book from 1893 refers to mashers as wearing tight jeans and attempting to woo any woman who would cross their path! Theatrical and Circus Life, by John J. Jennings, describes the masher as a character who may be of any class or profession, their dissimilarities obliterated by their shared enactment of “flagrant and audacious” behavior towards women.

The subject was even tackled in the early days of the movie industry in silent film shorts such as Percy, the Masher (1911) and Murray the Masher (1912).

Women Fight Back

Many women were fed up with the ways they were being treated in public, cornered on pubic transit and bombarded with verbal assaults. As time went on reports of women using their hatpins as weapons against mashers began to surface in newspapers.

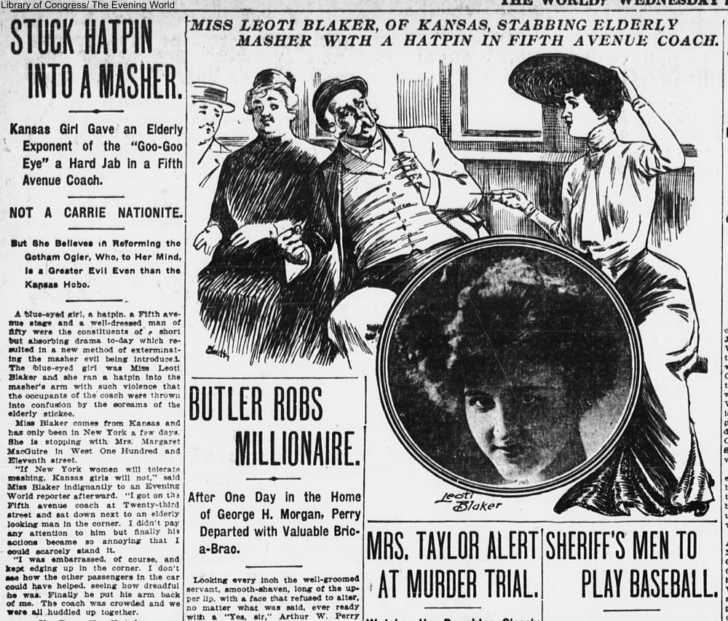

This section of the evening edition of The World newspaper from May 1903 (shown above) features a drawing of Leoti Blaker stabbing a masher with her hatpin on a public bus. Note that the article mentions she is not Carrie Nationite, meaning that she wasn’t part of the Temperance Movement. Women like Carrie A. Nation at the time were swinging axes for Temperance to great public criticism and the suffragettes were none too popular either.

The mention of Blaker’s political non-affiliations attempted to show her as an average woman, devoid of radical views. The article goes to great lengths to prove Blaker was justified in her actions – sentiment mirrored in the rash of stabbings around the world as a response to street harassment.

Hatpins had become the lady’s way of defending herself and many cases made the news around the turn of the century, as young women trained to use their hatpins in groups such as the Young Ladies Protective Association of Education Hill.

Backlash Against Hatpins

In widespread retaliation against women using their hatpins as weapons some cities passed ordinances prohibiting women from wearing hatpins.

Women were vocal about their disdain for masher behavior, but after the conflict surrounding women’s suffrage and the intense fatigue felt after both World War I and the Spanish flu epidemic, bigger issues seemed to loom over the whole world.

Ladies’ fashions moved away from large hats to bobbed hair and cloche hats, making hatpins largely obsolete. The issue of street harassment faded from the press like a cooling ember, and the term masher fell out of use. While the #MeToo and Hollaback movements have been looming large in the media, the original anti-harassment cause was taken up by ladies with hatpins who waged their own war – one jab at a time.

Click the “Next Page” button to read the sewing advice so sexist some thought it was fake!

SKM: below-content placeholderWhizzco for DOT