A Former Enslaved Man’s 1865 Response When Asked to Return to the Plantation

The letter remains a truly striking piece of history.

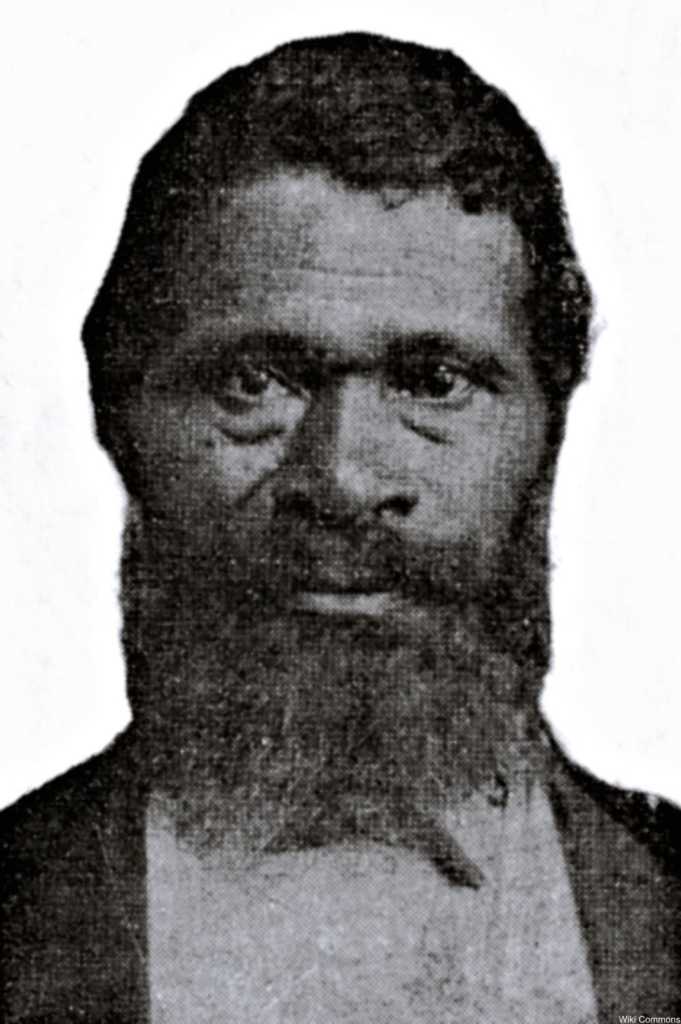

Once freed from a life of slavery in 1864, Jordan Anderson and his family headed North and made friends among abolitionists. For the first time in his life he was earning wages, $25 a week. Less than 2 years later, in a last ditch attempt to save his plantation, Jordan’s former master wrote a letter asking his servant to come back and the return letter from Jordan is a truly striking piece of history.

Freedom from Slavery

Jordan Anderson served his master, Colonel Paulding H. Anderson, for 32 long years in Big Spring, Tennessee. As Jordan left the place he had been enslaved since childhood, his former master attempted to shoot him twice before a neighbor intervened. Jordan was warned off the property by the Colonel for “deserting” him. Jordan and his family moved to Ohio, where his wife Amanda had relatives. In 1865 the Colonel wrote to Jordan to ask him to return to the plantation, claiming the place was falling to ruin without his (unpaid) right-hand man. That letter from the Colonel has been lost to time, but Jordan’s response remains with us.

Being illiterate, Jordan asked his employer, Valentine Winters, to transcribe a thoughtful letter back to the Colonel. The document is one of the few recorded instances of a former enslaved person publicly criticizing the gruesome practice of slavery, in no small part because to do so openly would have had disastrous consequences.

The Poignant Letter

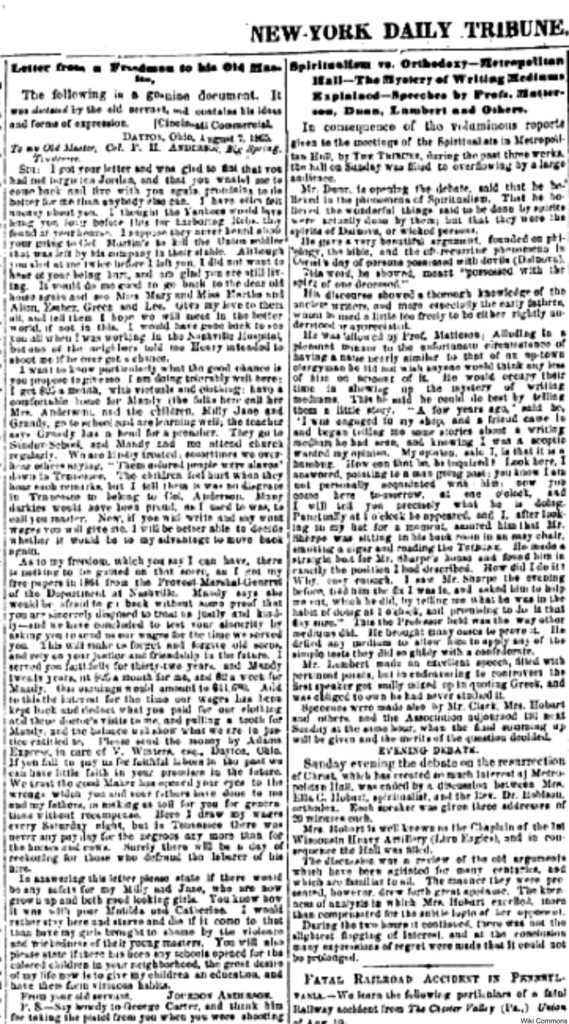

Jordan’s letter, being of such note, appeared in the Cincinnati Commercial newspaper under the title “Letter from a Freedman to His Old Master” after Winters, a staunch abolitionist, shared it with the publication. The letter was later picked up by other newspapers and was even published in other countries. It was newsworthy then and remains so to this day for the intelligent satire and thoughtful dignity the letter conveys.

From Jordan’s 1865 response: “I am doing tolerably well here. I get twenty-five dollars a month, with victuals and clothing…and the children — Milly, Jane, and Grundy — go to school and are learning well…Now if you will write and say what wages you will give me, I will be better able to decide whether it would be to my advantage to move back again.” Jordan goes on to state that the promise of wages would entice him and his wife to “forgive and forget old scores.”

Jordan then asks a pointed question: will the Colonel provide the back wages for 32 years of unpaid service for himself (and 20 years of service for his wife) before they make any move down there? The sum calculated by Jordan was $11,680 plus interest – doctor’s visits, clothing, and other expenses to be taken out of the final sum.

Obviously, no such deal was struck and the Colonel died only 2 years after, having sold his land not long after Jordan’s letter was dictated and published. Years later the Colonel’s children were reportedly still angry at Jordan for not returning to the place where he was kept as a slave to their father.

Jordan signs the letter “from your old servant” but not before asking the Colonel to thank the neighbor for taking the pistol away the day that Jordan and his family left the plantation. You can read the letter in full here.

Jordan died in 1905 and his wife some years later and their descendants still live in Ohio. Today Jordan’s letter remains a sterling example of thoughtful, satirical commentary on slavery by a man who lived through it.

Click here to read about a former slave who became the First Lady’s go-to dress designer.

SKM: below-content placeholderWhizzco for DOT